Episode 164 | Juana Estrada Hernandez

Published November 2, 2022

Episode 164 | Juana Estrada Hernandez

In this episode, Miranda speaks with Juana Estrada Hernandez. This episode was recorded in Miranda’s casita in the middle of a Santa Fe monsoon! They talk about her practice exploring the immigrant experience and border politics, her newly minted MFA, and her experience as a DACA recipient. They also get into the importance of voting and how those who can vote have the responsibility to do so. For more resources for voting on Nov 8th go to www.vote.org!

Miranda Metcalf 03:12

Hi, Juana. How's it going?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 03:13

Good. How are you?

Miranda Metcalf 03:14

Good! Welcome to my home.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 03:17

Yes, thank you for hosting me in your beautiful Santa Fe casita.

Miranda Metcalf 03:21

Thank you. Thank you, yeah, this is a Hello, Print Friend first. You are, I think, the first artist I've recorded in my house. Like, I've definitely done in-person recordings, but they've always been out in the field, at Print Austin or something like that. And so this is really fun. It's like getting to have a talk while we get to watch my dogs walking around the house. Hopefully they'll be good.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 03:42

Yes, no, they're lovely little dogs. But yeah, thank you for opening the doors to your home. And it's just exciting to be back in Albuquerque.

Miranda Metcalf 03:50

Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. As we'll get into, you have some roots in educational history in this part of the world. So I'm sure we'll get into that in your story. But before we do, can you just introduce yourself and let people know who you are, where you are, what you do?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 04:08

Yep! So my name is Juana Estrada Hernandez, and I am a printmaking artist working as - well, recently, working at as an assistant professor of printmaking at Fort Hays State University. I am originally from Luis Moya, Zacatecas. And my family and I migrated to the US in the early 2000s when I was seven years old. And I was raised for most of my life in Denver, and once I started jumping from high school to undergrad and grad school, I've just traveled ever since.

Miranda Metcalf 04:44

I feel like that's dividing childhood sort of right down the middle, right? So you had the first seven years in one part of the world, then you moved. What was that like in terms of your artistic development? Having one culture, one set of inputs leading up until seven, and then probably one quite different from seven? Do you think that that affected the way you perceive art and art making?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 05:08

I think it changes the way that I think art has to, or should, function in some ways. Art has always been a really large part of my life. So when I did finally move from Mexico to the US, my family - and I'm sure a lot of people who have to migrate - there's a lot of transitions that happen with language, assimilating to new cultures, and all that in between. But for me, art was something that I used to communicate when I didn't know how to speak English. And so even though I moved to the US at a very early age - and I feel like a lot of my teachers told me that it would have been easier to learn to speak a new language - I always had, like, a learning curve. It took me a little bit longer to do that. And so going through school in those early years, art really just... I don't know, in many ways, it... I've always drawn in school. I think that's the story of a lot of artists, we were just spacey people.

Miranda Metcalf 06:10

Yeah, the doodlers.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 06:11

But for me, it was therapy in many ways. But then also, it was a really literal way of communicating with people what things that I needed. Sometimes, I'd be in the classroom, and I wouldn't know how to say something, so I would just doodle it. And hold up my little sketch and say, 'This is what I need.' And so using visual language to communicate when I didn't have the words has always been... I don't know, in those moments, it was really life saving, in many ways. But then also, as I got older, sort of trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life, I felt like... it just feels like art has always come in at different moments in my life where I needed it to communicate with people. And I think it's still functioning in that same way now. But at least now, I've been able to learn how to speak English and communicate orally. And... I think I'm just ranting now.

Miranda Metcalf 07:08

No, no worries. I think that's all really good and interesting, because it sounds like art had this place in your life - [like] you said, with a lot of artists, where it's something that you do in school - but also had a real functionality for you early on, I think, in a way that for many people who didn't have that experience, they wouldn't have had that direct connection between art and communication. Because I think a lot of times when kids are just kids, it's like, oh, here's a bunny. Here's a rainbow. And it doesn't have that direct communication and that real purpose within a young artist's life. Yeah, for sure. What's your earliest memory of art and knowing that this is a thing that someone can do with their life?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 07:50

To be honest, I wasn't really sure if being an artist was going to be something that I was going to be able to do. Because I think that being a migrant, I don't think that's something that you always have a choice for. It's really... going through school, I really thought I had to be a doctor or a lawyer or just something that, for sure, there was a guaranteed possible job after school.

Miranda Metcalf 08:18

Yeah. Do you think that was something that you got from your folks, or just the people around you? Where'd that come from?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 08:25

I think it was a self-placed pressure. Growing up, my parents... we moved to this country to have the freedom to have the life that we want. And yet at the same time, it's, okay, well, to prosper in the US or to get out of poverty, maybe being an artist isn't the direct choice.

Miranda Metcalf 08:44

It's not the stereotypical one, that's for sure.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 08:47

Yes. But also, I didn't really have models in my family to feel like I had that choice. Until, when I got to school they were like, 'Oh, hey, it looks like you really like doing this. Have you thought about being an artist?' And in high school, we had this program where... it was a science ready program, so that if you wanted to go into the medical field, you could take classes that could prepare you for that. And so, for a long time, I was like, 'Oh, yeah, I'm gonna be a doctor.' And I really enjoyed the science. But then I started taking this class, and I was like, 'Oh, no, I don't want to do this.' And they had assignments to do medical illustrations of the things that we were learning. And so then for a while, I was like, 'Oh, yeah! I can do medical illustration.' But then when it came time to figure out how to go to school for that, I was like, 'Oh, yeah, I can't afford to do that.' So that didn't happen.

Miranda Metcalf 09:43

Yeah, I don't think I realized that medical illustration was still a thing. It seems like... you would think that would be the kind of - almost old fashioned, but of course, now that I'm thinking about it, it would have to be... that didactic drawing is something you can't really take a photo of. Because you - I guess I'm thinking about it in terms of the human body - but you can't pull out a tendon that's sticking straight up and just point to it, or something, that just couldn't actually happen in photographs. Oh, interesting. And so you realized that medical illustration wasn't gonna work, and so at that point, were you thinking about the fine arts?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 09:43

No, not yet. So that was towards the end of high school. And during that time - well, not only did I realize that it was too expensive for me to go to college for medical illustration, but a lot of people - during that time, I also was going through this experience where I've always known that I've always been undocumented. There's these social understandings that happen with navigating the world with this status. But I guess I didn't really, truly understand what that really meant. The implications of pursuing higher education.

Miranda Metcalf 10:58

Yeah.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 10:59

And so that was early 2011. And so it was a really stressful time, to be honest. I had to figure out - I had the grades, I thought I had the work ethic, I had the drive to go and pursue college - but I guess I just didn't really understand that, oh, yeah, being with this undocumented status, you can't qualify for FAFSA, get a driver's license, do these rite of passage things that happen in high school. And then a year later, when Barack Obama passed the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals in 2012, it was like a saving grace. And - that's [what] DACA [is short for] - and so during that year, I had other undocumented friends who ended up finding a university called Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kansas. And I was like, 'Hey... you're on DACA. How did that happen, since we can't apply for FAFSA?' And they said this university had a lot of scholarships. They didn't care about your undocumented status.

Miranda Metcalf 12:02

Oh, that's great.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 12:03

And so when I finally got out to Fort Hays, I went to the - and hopefully, Hector Villanueva will hear this - but Hector Villanueva was the academic recruitment advisor for the Access Opportunity Grant at that University. And he went out of his way to come to Denver. So long story short, I got all the scholarships that I needed to attend this college, it was almost like a full ride.

Miranda Metcalf 12:29

Oh, wonderful.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 12:29

But my parents, this was the first time that I was - like, I'm also the first person in my family to go to college. And they were not going to let me go, because it was out of state.

Miranda Metcalf 12:39

Was it too far?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 12:41

It was too far. And I think they were just scared. I was the first person that was gonna go to college, they didn't know how to navigate that. Both my parents didn't - they only got as far as fifth and sixth grade. And so navigating academia was something that they'd never experienced. And so Hector, he was the person who was helping me to apply for all these scholarships. And I basically said, 'SOS! Hey, Hector, can you come out and speak to my parents? Because they are unsure of allowing me to go.' And so Hector drove his little car from Hays, Kansas, all the way to Aurora, Colorado to talk to them, and he made it happen.

Miranda Metcalf 13:19

Oh, my gosh!

Juana Estrada Hernandez 13:20

And there's a lot of people that I thank for my success, but I think that he really saved my life.

Miranda Metcalf 13:31

That's an amazing story. And I think we will definitely send this to Hector, because I think the... I've had that - not that experience, but I've had moments in my life where it just seems like there are people who, for almost no reason, just decide that I'm worth something. And worth fighting for. And that's something you can't ever pay back. You can just hope to be able to do that for someone else. And so it's just a beautiful story. Yeah. What do you think it was that he said to your folks that let them know that it was going to be okay, and that this was important for you to do?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 14:12

I think just during that meeting, he really broke down what the college life was going to be about. And he talked about the campus culture, the classes that were going to be involved, but also, he talked to them in Spanish. He's also Hispanic. And I think that it really helped them to see someone that looked like us. And say, 'Oh, wow, he's in higher academia,' and he seemed to - I think it was just a perfect scenario, because I think he made them feel comfortable. He was clear, he was honest, and I think he just genuinely cared. And I think that's what they needed to see. 'Til this day. Hector doesn't work at that university anymore, but he still reaches out and asks how I'm doing. And he asks about my parents. And I think Hector really cared about not necessarily just raising the numbers for our institution that I currently work for now, but he genuinely cared about creating community.

Miranda Metcalf 15:14

Yeah, yeah. And people who, I think, see their roles, particularly in academia, as a way to actually affect positive change are some of the most precious people. Because there's so much administration in academia, I feel like, that's just weird and soulless. You know? I've got family who are professors, and it's just, yeah, talking to them sometimes, it's like, oh my gosh... so that's wonderful. And so what was it like for you, as you said, being the first one in your family, so you're really setting out in uncharted waters - I'm sure you had friends who had gone off, but in terms of your immediate family, you were the first - was this exciting? Scary? Did you feel like you were ready?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 16:00

I felt like I'd been preparing for this moment, when I finally got to undergrad, all my life. This is something that my parents were like, 'Okay, you're gonna go through the motions, and this is the last step for you to be whatever you want to be.' So it was exciting. But it was also scary, because I was like, 'I can't fail any classes!' Because there's also... again, financially speaking, it was such a miracle that I got to that place, but I don't know, I just enjoyed it. And then also, I think that this university was small, and it was intimate. And I don't know, it just gave me space to just do what I had to do.

Miranda Metcalf 16:39

Yeah, yeah. And when you arrived, did you know fine art was what you were going to do at that point?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 16:44

It's funny, because when I got there, Hector was under the understanding that I was going to be a neurophysicist. And so I signed up for all the science classes, because still, I felt like, oh, you know what, I can take art classes on the side and still pursue that and enjoy that. But also, I need this more practical job. And then I showed up for my first classes that first week, and then I said, 'You know what, Hector, I can't do this.' And he was like, 'What do you want to do?' And I said, 'Well, I want to get an art degree.' And he was like, 'Well, that's totally different. Because your grades are not reflective of... like, your grades are really great. And they're really reflective towards that science path.' And so he was like, 'Okay, well, bring me your art. Let me see your art.' And so I brought him a few paintings that I had made in community college, and drawings, and he was like, 'Oh, wow, you're actually pretty good! Okay. That's good.' He was like, 'Go for it, then.' And I think he just wanted to make sure that I was serious and that I wasn't... like, I felt like that was a real passion. And he was like, 'Okay, cool!' [At first] he was like, 'I just thought you were one of those people who just doodled for fun...' and just thought... I don't know. I don't know what he thought.

Miranda Metcalf 17:54

Well, I mean, I could see it, especially if you see a young woman with a lot of talent in STEM, wanting to see that be pursued. And it's your life, your choice, but yeah, wanting to just make sure that it's okay... Juana can just do everything. So this is fine. Yeah. And - oh, we're gonna have some Hello, Print Friend ambiance. We've got a monsoon coming through the house right now. The mic's picking it up a little bit, but that's cozy. So do you think that early interest in that - astrophysics, right?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 18:37

Right.

Miranda Metcalf 18:37

Yeah, I feel like that's the joke that people make when they're thinking of something very hard to do. Like, 'It's not astrophysics,' right? Do you think that early interest in science, does it show up in your art at all? Or was that really more of a practical choice? Or was it a passion that sort of finds its way back into what you make?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 18:57

No, I would say it was definitely a practical choice. I mean, I've always liked learning how things are made, how things are taken apart and put back together, and how things... how things are made. And I felt like, I don't know, it was really interesting, and it was really engaging for me. But I think in some ways... I don't think necessarily the science shows up in the work, but I think printmaking is so process-based, there could be a lot of chemistry involved, and so there are things that I continue to learn about print, and things that are continuously being discovered and pushed, and so I think that sense of excitement for science and alchemy, and things like that, are still in there.

Miranda Metcalf 19:46

And process. Yeah, that makes sense.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 19:48

And process. Yeah, I definitely would say that... I do wonder sometimes what would have happened if I pursued a path like that, but I don't know. I don't regret it.

Miranda Metcalf 19:58

Yeah, totally. Totally. Yeah, who knows? Maybe you'd be out working at Los Alamos or something, honestly. Who knows. And so, when you first discovered printmaking, was that in your undergrad?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 20:12

Yeah, it was. So when I finally did that switch from science to an art degree, the only thing that I had left - based off of what was left over in the classes that were available - was printmaking. And so the night before - I'd never heard of printmaking. And I think this is pretty common for a lot of people - I'd never heard of printmaking before, and so the night before, I'm like, 'What is printmaking?' And the first things that popped up on Google were screenprinting, like, you can make shirts! And so I just remember not going very far down in my Google search. And so I just showed up the next day thinking, oh, cool, we're gonna make t-shirts with screenprints, and make clothing, and I don't know, things that are more commercial. And then I ended up not learning screenprinting at all in my undergrad. But after that first semester, I was like, 'Oh, my God, this provides a little bit of everything!' Drawing, painting, working with your hands. And I don't know, I just never turned back after that. It was such a really exciting class. And yeah, it was just like a love at first sight. I think I got halfway through that first semester, and I just said, 'I'm going to be a print major.' And that was it.

Miranda Metcalf 21:26

Oh, that's great. Yeah, yeah. And so what was your early work like?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 21:31

It was still very figurative, like, representational. It was... I think a lot of it, in terms of the theme - there's a lot of overlap - but a lot of the early work was just still figuring out my place in the world, trying to figure out what it meant to be a DACA person. Giving myself time and space to figure out what it meant for me, what it meant for others who were in this place. But then also, there were just a lot of bad prints! With trying to figure out process, and understanding how things worked. But visually speaking, they were very dark... because I think that even though, starting college, you should be in a very exciting time - which it was - there was still a lot of tension, because a year before, I wasn't really sure what my life would have been. And then DACA just showed up, and I was like, 'Oh, awesome. Now I can take a step forward, not five steps back.'

Miranda Metcalf 22:27

From talking to other people, what I understand is that the only choice would be to return to whatever country someone's from, and then wait and try and come as an international student, which would then be this whole 'nother long process. And of course, as you said, there's no financial aid for international students and all of it. So yeah, I see what you're saying about the stepping forward versus stepping back. Was there any sense of being able to process what you'd been through in that early work? As you said, the uncertainty, and then the certainty, and then the uncertainty again... [those are] some big, dramatic experiences to be having as a young person that a lot of people who are going to college don't have to experience. It's just, 'I just wanted to get into at least my safety school,' right? Did that come out at all in your early making?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 23:17

Yeah, definitely. It still hasn't gone away. Because even though DACA did start in 2012, it's still... actually, as of last week, it just got sent back to court, and they're deciding whether to take it or leave it. And so this level of uncertainty, I don't think, has ever left since the program started. But in some ways, I'm still living in survival mode. And I'm not really sure, even if... if DACA were to be, I don't know, like if there was a different pathway for me and the other 600,000 people, I think that a lot of us have been living this way for so long that I'm not really sure what it's like not to live that way. A lot of people say, 'Oh, that's really sad.' But at the end of it, it just is [what it is] as of right now.

Miranda Metcalf 24:09

Yeah.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 24:09

But as far as the early work, I really tried to... there was one thing that my undergrad mentor said to me very early on. His name is Gordon Sherman, who recently passed away. He basically was like, 'Well, you're making-' the first year, I was making images of skulls and animals, and things like that - and I remember him saying, 'Well, this is great and all, but I think that based off of the things that I've learned from you, and all the stories that you shared with me, it seems like you need to, if you're ready, allow space for that.' And he kind of... I don't know, I wouldn't say he gave me permission, but he was like, 'It's okay to do this with your work. And maybe this is what you need to do.' And I was like, 'Okay...' you know, I was really young. I was like, 'Okay, whatever.' But once I started making prints about my family's migrating experience, it just started to drive my work in ways that I couldn't have foreseen before then. But yeah, it gave me almost this drive to really... there's a power in making political artwork, and there is power of sharing stories of the things that people have experienced in the past, present, and maybe will in the future. And I think that for me, because I was a part of the new DACA wave, I felt like at that moment, if miraculously I got to go to school for art - where, again, I wasn't sure if I was ever going to be able to - then I'm going to use my art to make a difference. And to basically use my work to create a platform for people, for others. There's a lot of people in my community who are afraid to say, to expose themselves and their statuses and things like that. But I think that there's also a lot of power, and that it doesn't... I think it's important to know that we are here, and accepting that it is okay to share our stories. It was just a really helpful thing for me early on. It made me feel like my voice mattered, and that I could change the world.

Miranda Metcalf 26:11

Yeah, that's beautiful. That's really beautiful. And everything you said makes a lot of sense, particularly in regard to the power of storytelling. And, I would imagine, telling your own story from your own perspective. Because as you say, there are a lot of trepidations about people coming forward with their documented status, for good reason, because there can be consequences. But without the voice of undocumented people in the world, then there's no narrative that comes from them. And it's only things being projected onto people who are undocumented. So being able to be a voice that's actually creating a narrative from the lived perspective of the human who's gone through this is incredible work.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 26:55

It has to happen that way. And a lot of my recent artwork that I made in grad school, I was going through grad school during the Trump administration. And we can talk a lot about the things that we disagree on, as far as everything that they did and changed, but their administration, I think, was the most vocal about their distaste for migrant communities. And they're continuing changing policies to attack migrants. Like for me, they went after DACA, and they failed - which, hooray for me, and hooray for the rest of the folks who have the status - but then they also went after people who were fleeing violence in lots of places in Latin America, with the zero tolerance policy that was separating families on the US southern border. So during that time in grad school, I think it really propelled that... I suppose it really pushed me to keep talking about my stories. Because there was a lot of misrepresentation in the media. And so I was like, 'Well, wait a minute, that's not accurate.' And my nieces - I now have a nephew - but around 2018, 2019, my family came up from Denver to visit me in Albuquerque. And it was their first time driving up. And they brought my oldest niece and, at the time, she was eight years old. And when they finally got to Albuquerque, they my niece was like... she just got out of the car and was asking me a lot of questions. And a lot of them were like, 'Hey, where do we come from? Where is Trump's wall? My grandma and my grandpa were saying that we can't go anywhere near the border, or we can't go to Mexico because we can't come back.' And so for her, she was like, 'What?' She had a lot of questions. And she was like, 'Because on the news, I saw that they were saying that we are bad people, and that we are doing A, B, C, and D.' And so she was experiencing this really skewed, negative perspective of her own family. People in our community. And so she was like, 'Well, what's going on? Because that's not true. Because I'm being raised by all of you guys. And we're not bad people.' And so I had the privilege of, I guess, in some ways, knowing more of where I come from, like she's now second generation. And so she had a lot of questions about, yeah, where do we come from? And why did we come here? And how did we get here? And what were we doing in those first early days moving to the US? And things like that, while also trying to push away that negative perspective that was being presented in the media. And so for me, after that trip, I was like, 'Oh my god.' It solidified the sort of responsibility that I gladly took to say, okay, I really need to share my family's history, our oral histories and traditions. And really push that into the work, while also not forgetting that there is a lot of pain and trauma that happened within my family history of moving to the US. But then there's also a lot of beautiful things that have happened as well. My niece. Like, she just happened because of that. So yeah, I think it is important to have people be able to voice their stories. And not allow... yeah, because once other people that are not from your culture or your community start sharing your stories, it's... I don't know... it doesn't make sense to me. It's just not their experience.

Miranda Metcalf 30:52

Yeah. Well, exactly, and it's going to be altered in some way. There's just no... even people with good intentions, just passing through another human experience, something will change coming out the other side.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 31:07

Right.

Miranda Metcalf 31:08

Yeah. So in terms of how these narratives - you said, both the beautiful and the traumatic, and probably everything in between - how do they show up in your work?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 31:20

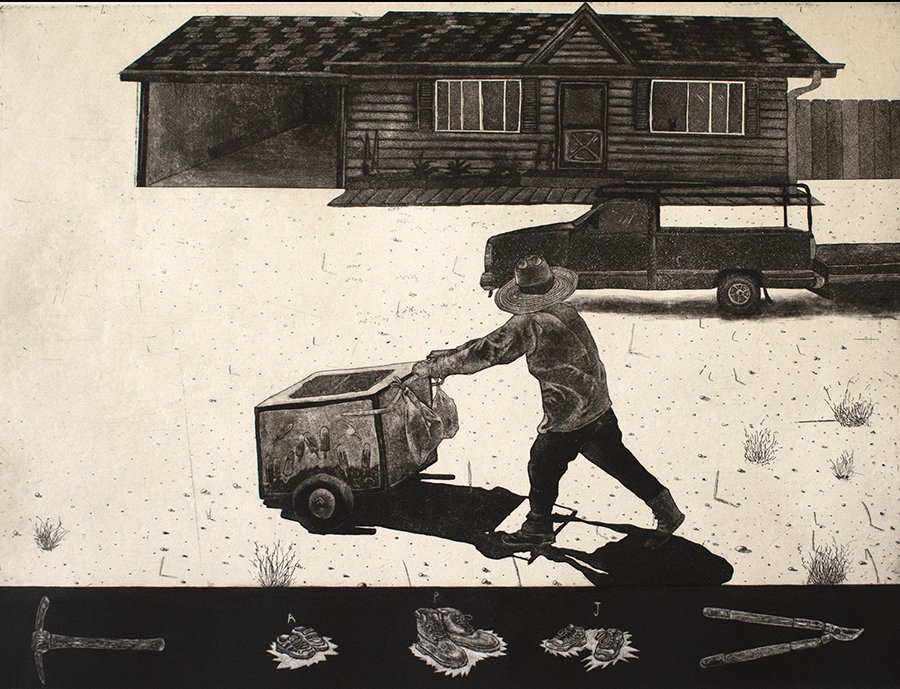

Yeah, so a lot of my work focuses on, I would say, nonlinear intergenerational stories that are done in collaboration with my mom and dad, my nieces and nephews, sometimes my aunts and uncles, my siblings. And as of recently, I've been making a lot of - I genuinely like all the processes in print - but I've been doing a lot more lithographs as of late. And I think, because it just reminds me of that... it's like a very direct process. But I've always loved to draw. And so it just feels like one of those natural choices. But I have prints that show my family celebrating a party with a pinata, so it's thinking about the traditions that we brought to the US. There's a lot of prints that have food in it. And so really uplifting those traditional foods that we brought with us. There's prints that show... there's one print with a little boy and a slingshot that I presented in SGCI this past conference. A little slingshot with a nopal, trying to shoot ICE, so talking about the ways that ICE still affects our immigrant communities. And they're just kind of all over, all over the map as far as stories. But yeah, it's just a lot about showing my family members within them, showing different aspects of my culture, like food. And not only just drawing food, but also the colors. Like, I've been making more colorful prints [that are] reflective of my home. And then sometimes, too, there's writing that shows up in the prints as well. And when I do write on the prints, sometimes it's forms of questions, or... and they're always in Spanish. Because I think that... I feel like there's always the question of, who is your audience? Going through art school, like, who did you make this for? Who is this intended for? But I think it's, once you put the work out there, you never know who's gonna see the work. Sure, you can be very particular as far as where the work is going to be exhibited. But at the end of the day, it's open to the public. And for me, I still wanted to have - as far as like, my choice of using Spanish - for one, it makes me feel connected to my family, to my culture. But also, I think that it's important that if this work is about my family, it's for my community, it's for my family, then there has to be some sort of connection there. And for me, I choose Spanish to do that. When I presented my MFA thesis show last December, I specifically picked a place in Albuquerque, in the burlesque neighborhood, because I didn't - well, I didn't necessarily like the spaces that were available on campus. But I felt like it was really important to get my work out into the community. When I presented it, I drew directly on the wall. And on the wall, there were a lot of questions to guide the story that I presented. But when the public started to come in to the show, there [were] actually a lot of little families, Hispanic families. And of course, my mentors came in, my grad cohort and friends came in, but when I saw these families come in and see the work, I really saw them engage with the work in a way that I've never seen before. And what I mean by that is that they really sat with the work and read the questions. And they started to talk about their own stories in the space, which is something that I never could have anticipated. And for me, that was really humbling and exciting, because here I am presenting this body of work that shares my family's migration stories, and their triumphs, and the pain, the things that we've experienced as immigrants living in the US. And yet there [were] other people coming in - and of course, as a culture, we're not a monolith. Everybody has different experiences - but these people were coming in, and they were talking about their own experiences. And I went over to some women, and I just talked to them in Spanish, and said, 'Hey, what do you think about the work?' And they were like, 'Are you the artist?' And I was like, 'Yeah.' And then they were like, 'This is not how you say that!' And I was like, 'What do you mean?' And she said, 'It's actually...' I can't remember what it was. But she was like, 'This is not how you write this.' And I was like, 'Well, where are you from?' And she was like, 'Well, I'm from Chihuahua.' And I was like, 'Well, I'm from Zacatecas! We say things differently.' And... yeah, she was a very sassy person. But it almost created a pod, or like, a safe space to share stories. But then also, too, there's a lot of people who feel surprised that anybody would take the time to depict them and their stories. And my mom and dad have always said, 'Well, why us? Why does anybody want to see us in the gallery? Or in the museum?' Like, they don't feel... I don't know, they're very confused about that. And so for me, I'm like, well, why? I think that our stories matter. I think that you matter. I want to see people that look like me in institutions, a gallery or museum or a university or all these things, because it does matter. But they're always so surprised. And these families that came in during my show, they were just so surprised. They're like, 'Oh, wow, these are our stories.' And in some loose way, there were a lot of intersections that they had with mine. I think that's why it's important for me to keep making my work. Because I want to live in a world where it's not surprising to see brown people in a space. Or to have people just be surprised that they can see themselves within the white gallery walls.

Miranda Metcalf 37:19

Yeah. And I think that's something that, for a lot of people... it's sort of invisible to them. When your identities are the dominant narrative, you don't even question it. I think it really speaks to how, when you only have people who are the dominant narrative creating the dominant narrative, that it will never, ever, ever change. And I think just really, in the last decade or so, I think you're seeing major culture producers like Disney realizing the value of having other narratives, just something else, you know? ...Not that I would ever think Disney is altruistic, I think they probably realized they could make money on it, of course. And I think we're starting to understand the real emotional gravity of that for people who haven't been seeing themselves in visual culture, in museums, as you say, in movies. And so I would hope that we're kind of starting to move the needle on that a little bit, in many ways. And so you find artists like yourself working, and then also in pop culture as well, maybe we are, hopefully, moving towards that. As you say, that time when it isn't shocking to people, and maybe your niece and nephew, when they have kids, it won't be as shocking. But it's important work. And it's important to be able to give people opportunities to be in the situation to be the culture creators. For sure.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 38:51

Yeah, for sure. And I think as far as changing who is represented in different spaces, I think that there's still a lot of work to do. But I think that... the wave is starting to part, and there's starting to be more room. But I think also, we're seeing this wave of new printmakers, new curators, new gallery owners, new shop owners that are all for that. And I think that's what we need. People who are going to open those doors. And even if there [aren't] people who open those doors, well, hell, let's make our own spaces. You know, that's okay, too. And maybe that's even better.

Miranda Metcalf 39:28

Totally, because, yeah, again, as you say, when your narrative passes through someone else, it's going to change. You know? And so if that gatekeeper is still someone else, it's altered. Yeah, for sure. So you have a relatively recent MFA -was it last year that you graduated? 2012? Sorry - 2012. I'm so dyslexic - 2021?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 39:53

Yes, December 2021.

Miranda Metcalf 39:54

So that means that your MFA experience was probably greatly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 40:03

Yes, it did. I was supposed to finish in Spring 2021. But I decided to extend another semester. And I think a large part of that decision was just because of the pandemic, there was a lot... I'm sure there's a lot of other folks who can connect with this, but there were just a lot of shops that were closed, access to studios. And I guess I just felt like I had lost a semester to the pandemic, and I thought it would be okay to stay for another. I've been in school for so long, I was like, 'What's another semester?' But then also, I felt like I finally hit a spot in where [I had] my handle on the techniques. Like, everything just was like, 'Oh, wow, I am not having problems with...' I don't know, a spit bite, or these nuanced processes. But then also, I think I just needed more time to process the things that we had lived through with the pandemic, but then also, I think I just created a more cohesive presentation for my thesis. I wasn't really sure if I wanted to pressure myself to hurry up and finish. Because for me, it was like, first of all, I wasn't really sure if I was gonna go to grad school, and I just felt like I had to finish it in my own terms in my own way. And if it had to be for another semester, then that's okay.

Miranda Metcalf 41:23

Yeah, yeah, I think that's really an important message for particularly young artists to hear, because there is such a pressure to just be constantly doing, making, producing on a deadline. And so to hear that it can be okay to just say, 'To do my best work, I need more time.' ...I feel like that's not something that artists really are taught, that that's okay. You know? There's so much pressure on producing anything, particularly in school.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 41:51

Yeah, 'cause otherwise - I think, too, at that time, getting out of this space of being sheltered in place - we had been staying at home for so long. And also readjusting to getting back into the world. Yeah, no, I'm glad that I stayed a little bit longer. And I think sometimes, even for me, it is hard to say 'I need more time.' Because I do like to keep myself busy. But I think at that time, I was like, 'Okay, I really just need more time.' But I'm glad that the finances worked out and I was able to do it. But yeah, making that choice of giving yourself more time isn't always as easy for everyone.

Miranda Metcalf 42:35

Yeah, it's definitely... things have to line up for it to work. But definitely, yeah, do it if you can. And so what was your final thesis like?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 42:43

It was... honestly, it was just really busy. I recently got hired for my first teaching position. I actually got hired the semester that I was thesis-ing. So like I said, I graduated in December 2021. But I started my teaching position in August of that fall semester. So it was really hectic. There were a lot of nights where I didn't sleep very well. I don't know, it was not the healthiest, I would say. But also, I think it was the semester where I felt like I really hit my stride with making. One idea just kept informing the next and the next. But then also, I don't know, it was like this really interesting excitement for what I was doing. Not to say that I wasn't excited with the things that I was making before, during grad school, but... I don't know what happened. And maybe it was just the delirium of having to teach during the day and then work at night, and then just do it all over again until it was completed. But yeah, thesis semester was a trip. But I do wonder what it would have been like if I hadn't had to teach.

Miranda Metcalf 42:56

Oh, gosh. Yeah.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 43:13

But either way, I think that the work that I presented was some of the most honest work that I've ever made. And what does... 'honest' [mean] to you? Early on, I felt like I made work... like, the work that I was making really was like, hey, let me share my narrative so that I can change your mind of not being anti-immigrant, or racist, or discriminative towards like other people who don't look like you. And when I [say] honest, it was work that shared my stories in a way that... there was not as much emphasis of "let me change somebody else's mind." It's "let me just... tell you my story." And I don't care what you think, because at the end of the day, I needed to do it for me. I needed to do it for the other generations of my family. I needed to do it for my community. And I do it because I needed to, for myself, and not for any other bigoted people.

Miranda Metcalf 44:59

That's such an important distinction, but one that, I feel like, feels really reflective of a lot of artists' journeys into being a mature artist. As you said, you're often asked to think about your audience - of course, that's part of the training that we get as artists - but that ability to find... not knowing that you've got an audience out there, but making work because you need to see it in the world, not thinking so much about its reception, I feel like is something that... you can only get there by just making a lot. Building up that understanding of yourself, and all of it. Getting to the point where you can just be like, 'No, this needs to exist for me and for the people that I care about.' Yeah, it's a very cool place to be, I think. So what are you looking forward to? What do you have on the horizon that people can keep an eye out for?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 45:51

I have a couple shows coming up this year. But I'm just hoping to be able to make new work and things like that, but I really just need a future where... my future is stable. And so I feel like that's just a very... I don't know when that will be. But now, going through school and starting my first teaching job... Yes, teaching is going to keep me busy. And I enjoy it. I'm going to have more shows coming up. But I just really need time to live without an unstable status. And I want that for other people as well. And... Grandpa Biden needs to hurry up and do something! Something for our communities. But yeah, as far as the tangible things that are coming up, I have a solo show coming up in the Hecho a Mano Gallery in Santa Fe, and a two person show with Humberto Saenz at the Janet Print... or, no, what is it... Janet Turner Print Museum.

Miranda Metcalf 47:01

In Chico, yeah.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 47:02

Yep, in Chico, California.

Miranda Metcalf 47:03

Yeah, cool.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 47:04

But yeah, so that's what's coming up. But yeah, I guess for those who will be, hopefully, hearing this podcast in the future, I really want all of you guys to just stay informed, of course, about what's happening in the world. And, yeah, sometimes we do need to shut off from all of the things that we don't like that are happening in our communities and things like that. But we just have to stay informed and see what's happening with other communities. And for me, I mean, I'm very passionate about what's happening with DACA because of course, I am being affected by it. But it's just like one facet of a big problem that has been happening in the United States for a long time. Which is that there hasn't been, really, any tangible solutions for providing what the government has called "essential workers." Right? Like people who work in the agricultural sector, people who work in factories and things like that, people who kept our nation going during one of the worst times during COVID. And yet, there's still no relief being provided for us. So as far as what I ask for our communities, just keep your ears open. And if you guys can just spread the word about what's happening, do it. Because I think that... I don't know. It's just a conversation that keeps being cycled in my community. And there's never a solution.

Miranda Metcalf 48:42

Yeah. And as you're talking, bouncing around in my head [are] these ideas around how we're all Americans. [And] unless you're an Indigenous person, someone, not too long ago, came to this country. And the culture in America is very individualistic and very divisive, and you know, like the Hatfields and the McCoys. I mean, like, 'This is mine, you can't have it,' you know. And it's led to real strife, and just awful cultural climate in the States. It's just getting worse. And I feel like the only antidote to that is moving back into, we're all Americans. Trying to find that shared sense of what it is to live in this land and be on this soil and know that the vast majority of us are all visitors here. And that we need to understand how we don't survive unless we all survive. And as you said, people who kept the country absolutely going - like kept your strawberries in your Trader Joe's in Summer 2020 - they are American because they are a part of the American system. And it is an awful hypocrisy, particularly in this country, to make that distinction.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 50:01

Oh, for sure. Yeah, and you know, we live on stolen land.

Miranda Metcalf 50:04

Exactly.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 50:05

I don't care what you think your history is. That's what it is. And then, also, there were a lot of - I don't know if a lot of people know this or not - but there were a lot of people in the medical field who are also DACA, and were in the front lines of this pandemic. So you're right, there is a lot of hypocrisy, right? Where I think that we, as migrants, we have this hold on the "American Dream," but I think that within the "American Dream," there is a lot of hypocrisy. And that there is a lot of... I don't know... I'm not really sure about that word anymore. Because of the fact that, there's still so much work to be done. And yes, I think that there's still a lot of disparities that are happening all over the world. And yes, maybe we... like, the folks who are... I don't know, it's interesting, because I have family who still live in Mexico. And they're like, 'Well, despite the politics, you're still in the US, you still have been able to more or less live a successful life. It's been hard, but life is hard, but it's okay!' But with that conversation, I still want... there shouldn't be a choice between... I don't know, I think the understanding that I got is, even if things are hard in the US, you're still living a better life than you would have been anywhere else, where there's poverty and violence, and natural disasters happening all the time, and corruption, and things like that. But there's still a lot more that can be done for the people that live in the US. And... it just pisses me off that they say that we are essential workers, and we are still getting screwed at the end. We're given promises with every Democratic administration, and nothing happens. And yeah, that's why voting is important. But I just feel like there's still a lot of people in the government that hold back.

Miranda Metcalf 50:05

I totally agree. And I feel like you're voicing what a lot of progressive people feel, which is a deep frustration with the Democratic Party for not upholding the ideals that we hold. And... you're like, 'Yeah, let's take care of undocumented workers. Let's take care of health care. Let's give mothers paid maternity leave.' All of these things that everyone I know who identifies as a progressive person would love to see enacted. And yet, it just is this impotence, it seems, on the part of the Democratic Party, to actually do anything.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 52:54

Yeah. And then there's also the other side, that people who can vote, don't vote. And that is horrible! I can't vote. I wish I had a voice. But as far as electing whoever is going to run the place where I live in now... yeah, like, when I hear people who say things like, 'Well, my vote doesn't really matter,' I wish you could give me your vote! Because I'm sitting here with my hands tied, wishing that I could just cast my ballot, and I can't! And how am I more informed about the dates on when you have to register, or where you have to go, than the person who has the born, given right to do so?

Miranda Metcalf 53:36

We could definitely do a whole 'nother episode on that. It was really interesting living in Australia, where voting is mandatory. You're actually fined if you don't vote. Well, Juana, where can people find you and see your work and follow you and help inform themselves about what you're doing and your story?

Juana Estrada Hernandez 53:52

Yes, so I have an Instagram account called @juanaseemyprints.

Miranda Metcalf 53:58

Possibly the best Instagram print name out there, yeah.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 54:02

Yes. And you should think Chantal Bolinger for that. They're my partner. And yeah, they were like, 'Do something memorable, do something punny!' And they use puns all the time. I like puns, but then sometimes I'm like, 'Oh, my God, it's too much.' Like, I have 'Thank you, Dad' moments. And we can also thank Chantal for wrangling the doggies and keeping the doggies quiet during this interview, so thank you. Yeah, so you can find me on Instagram @juanaseemyprints. I also have an artist website called www.juanaseemyprints.weebly.com. And yeah, you guys, as far as where you can see my work in real life, it's just going to be like I said, I'm going to have some work in Santa Fe, some in Chico, some at 516 Arts, which is a contemporary museum in downtown Albuquerque, or otherwise, you can just come and visit me in Hays, Kansas and see my work there!

Miranda Metcalf 54:55

Wonderful. Thank you so much for coming out to my house and having a chat, it was really a treat to get to do this in person. So thank you so much.

Juana Estrada Hernandez 55:05

Oh, thank you so much.

Miranda Metcalf 55:07

If you liked today's episode, we have a Patreon where you can help us keep the lights on and get bonus content, like Shoptalk Shorts, where our editor Timothy Pauszek digs deep on materials, processes, and techniques with past guests. Also, if monetary support isn't in the cards for you right now, you can leave a review for us on your podcast listening app of choice or buy something from our sponsors and tell them Hello, Print Friend sent you. But as always, the very, very best thing you can do to support this podcast is by listening and sharing with your fellow print friends around the world. And that's our show for this week. Join me again next week when my guest will be Martin Schneider, founder of the Open Press Project. We talk about his creation of the world's first widely accessible 3D printed printing press, why he gives it away for free, and his traveling exhibition of tiny prints made on this special press. You won't want to miss it. This episode, like all episodes, was written and produced by me, Miranda Metcalf, with editing by Timothy Pauszek and music by Joshua Webber. I'll see you next week.