episode fifteen | aaron coleman

Published 29 May 2019

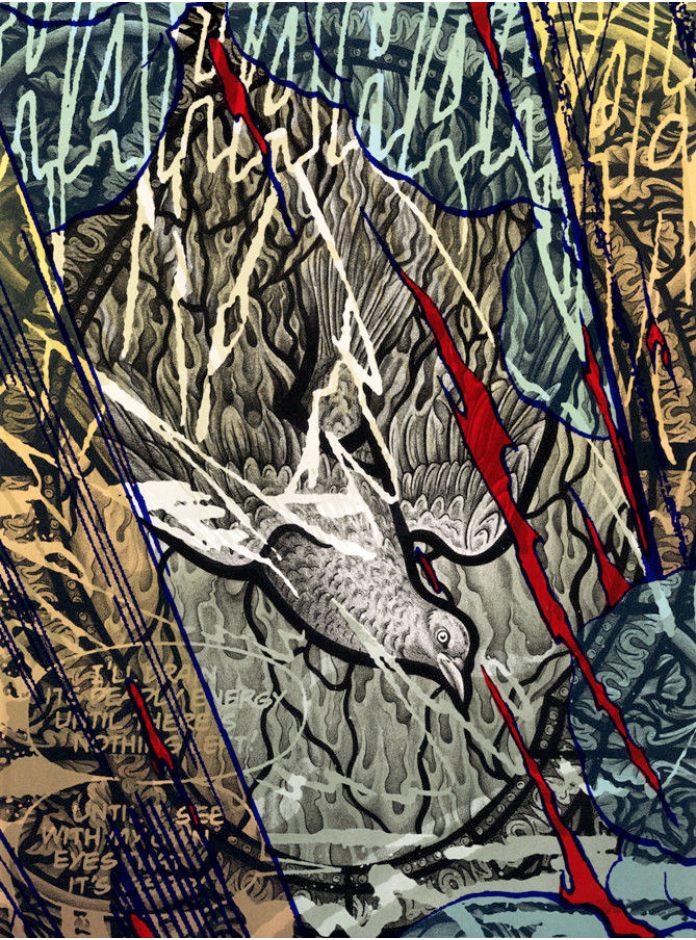

Survivor of the Great American Autoclave, 2015, lithography and screenprint, 16 x 12 inches

episode fifteen | aaron coleman

In this episode Miranda speaks with Aaron Coleman about his first exposure to visual culture as a graffiti writing teen outside of Indianapolis, his graduate school experience of being tricked into loving litho, and his current role as Professor of Art at the University of Arizona. The hip hop community was the first place Coleman really felt at home and the formative practice he experienced in the mixing and remixing of visual culture has stayed with him to this day. Coleman also talks about the place of art in the cultural of the resistance against the forces of evil in our world and the important role artists play as documentarians, communicators, and historians during our troubled times.

Miranda Metcalf Hello print friends, and welcome to the 15th episode of Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend), the internet's number one printmaking podcast. I'm your host, Miranda Metcalf. I release an episode every two weeks, and on the off weeks, I publish an article on the Pine Copper Lime website, which features images and maybe a bit more information about the artist I'm going to interview. My guest this week is Aaron Coleman, Professor of art at the University of Arizona. Aaron has been on my list to get on this pod pretty much since day one, because he's just the fucking coolest. His work is a drop dead standout from what anyone else is doing. At SGCI open portfolios, it can be difficult to even get to his table because of the crowd. It's stunningly rendered, wicked sharp politically, and full of a seemingly chaotic mix of medieval, Renaissance, and pop culture imagery. And what makes it truly fascinating for printmakers to look at, particularly in person, is that it can be hard to decipher which techniques Aaron has used to create his prints. Mezzotint, lithography, digital, intaglio, and screenprint all weave in and out of his practice with stunning depth. For anyone who has been following him on his Instagram, you might have noticed that recently he's revealed a series of incredible sculptures, which more than prove his skills in that medium as well. They are truly amazing and if you haven't seen them yet, please follow the link in the show notes to take a look. But for the love of God, Aaron, please don't abandon us over here in prints. In this interview, we talk about his early art influences in the hip hop community, being tricked into loving lithography by Michael Barnes, and the role of art in the political resistance. Aaron has this unique way of speaking that makes me feel simultaneously that everything is completely fucked up and it's going to be okay. I know you're gonna love it. But before we dive in, here's some quick housekeeping. First and foremost, if you haven't had a chance to check out the new Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend) online print gallery, give her a gander. I have beautiful work there from artists from all over Southeast Asia and Australia. And I still have the offer going on for listeners of Pine Copper Lime to get free shipping, including international shipping, with the offer code SHUN. That's right, as in the non believers. I also have the Pine Copper Lime Patreon up and buzzing, with levels starting at just $1 a month and gifts like postcards, stickers, tote bags, and more. But mostly, becoming a Patreon supporter is just a great way of saying Hey, I like PCL. I like that it exists. And I'd like to help it keep existing. And, as always, you know I'll love you forever if you tell a printmaker or two about Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend) and see if we can't grow this community even more. Printmaking forever, shun the non believers, join the party. And one last exciting announcement. The next episode of PCL, I'm going to be trying something a little different. It's going to be a bilingual double release. One version of the interview in English, and the other in Spanish. My guest for this is Marco Sanchez, a Mexican-born printmaker currently getting his MFA at Edinboro University, but grew up on the border town of El Paso, Texas. His prints address a number of things, like his relationship to his mentors such as his grandfather, to his cultural background in Mexican folklore, and most recently, he's been exploring the notion of immigrant identity and the current political climate of the United States. So make sure to join me then as well. It's going to be a fiesta. Alright, without further ado, here's Aaron. Hey, Aaron. How's it going?

Aaron Coleman Good. How you doing?

Miranda Metcalf I'm really good. I'm good. Thank you for joining me.

Aaron Coleman Of course.

Miranda Metcalf I'm super excited to chat. So before we dive into some questions, would you mind just introducing yourself briefly and letting the listeners know who you are and where you are and what you do?

Aaron Coleman Yeah. I'm Aaron Coleman, and I'm a human being. And I am on planet Earth. But more specifically, I'm a professor of art at the University of Arizona, I'm a printmaker, collage artist. I draw stuff. I paint stuff sometimes, but I make pretty terrible paintings. Yeah, I do all kinds of stuff.

Miranda Metcalf That's good. And how long have you been at the U of A?

Aaron Coleman I am finishing my third year right now.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah. So it's still still a pretty new position.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, it doesn't feel like that, though. In a good way.

Miranda Metcalf Totally. Totally. Well, I hope that that means that you're settling in nicely.

Aaron Coleman I think my permanent state is "settled in," no matter where I'm at.

Miranda Metcalf That's a very good quality to have. Sure. That's very zen of you. Well, I'd also love to hear you talk a little bit about your early art influences growing up, where that was, and what role art had in your childhood and anything like that.

Aaron Coleman Oh, man, those are big questions. I was born in Washington, DC, and I grew up in Waldorf, Maryland. I'm not too sure art had any influence on my childhood whatsoever. You know, I was kind of a bad kid. I was a good kid, but I was also bad. I was like running around, taking the wheels off of people's lawnmowers, and trying to make go karts out of them. And I would take my mom's watches apart, I would take the back off and take all the little pieces out, and then I wouldn't be able to put them back together. You know, I had a twin sister that I got into a lot of stupid stuff with. So I mean, I wasn't really like artistic or aware of art as a kid, I was just kind of like a curious, mischievous little guy. And when I got to be about 12 or 13, we moved to Indianapolis. My mom took a job in Indianapolis. So we moved. And I was kind of introduced to the hip hop scene and the graffiti scene around 13 or 14. And I think that was like my real first introduction to creative culture and visual art, if you will. So it didn't really come into my world until I was like an early teenager.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah. How did that introduction happen?

Aaron Coleman Well, I have four brothers, two of which lived with me for a long time, older brothers. And they always listened to hip hop, but I think I was kind of too young to really be into it. And so it wasn't until I got a little older, I would like steal CDs from them. And this was around like 12, 13, 14. And I started listening to the music that they were listening to when I was younger. I kind of fell in love with just hip hop culture, and the music and breakdancing and DJs. But a big part of hip hop culture is graffiti. And a lot of the guys that I went to school with were into graffiti. And so that was kind of how I found my way into that world. And before I knew it, I was writing my name on stuff that didn't belong to me, climbing up billboards, and going into the train yard in the middle of night, and all that kind of stuff. I was never really any good. But there was something about hip hop culture and graffiti culture that, you know, this idea that you could take from things that already existed and piece them back together in a new way. You know, like in hip hop, they're taking old music and making new music via sampling. And in graffiti, graffiti writers are kind of borrowing the environment around them to make it look the way they want or put their own message out there. So there's something really interesting to me about pulling from things that already existed to create something new. And so that's kind of why I attached myself to that world.

Miranda Metcalf And so that was sort of your first experience in visual making, was just really with the spray can or a big permanent Sharpie marker or something like that?

Aaron Coleman Yeah, we were a little more devious than that. We would fill refillable markers with glass etch and tag windows and actually etch our name into windows and things like that. We found out that the lava rocks around a McDonald's drive thru, like if you ever look at the ground around a McDonald's drive thru, there's a bunch of lava rocks on the curb, and we found out that those rocks could scratch into almost anything. And so we started using those to tag things that seemed untaggable.

Miranda Metcalf Oh my gosh, I wonder if the McDonald's Corporation has any idea the creative contribution that it's making?

Aaron Coleman Yeah, probably not.

Miranda Metcalf That is so interesting. And then so how did you go from that to art school?

Aaron Coleman Well, to be a good graffiti writer, you really have to not give a fuck about anything. You know, you're running from police all the time, you're out late at night, you've got to be out when no one else is around if you want to get up, and it makes things like normal relationships kind of difficult because, you know, graffiti is kind of irrational and aggressive and a normal-minded person might not understand the urge to go out and write your name on things or destroy property or whatever it is we were doing. And so you really have to not give a fuck about a lot of everyday normal things. And so I got sick of running from cops and I got sick of being afraid of getting arrested every time I was out tagging something, I just didn't have that "I don't give a fuck" bone in my body. And so I just wanted to do something that was less, I don't want to say dangerous, but less dangerous, less likely to get me in trouble. And also something that maybe seemed a little bit more legitimate, something that I could make a living doing. So I decided to go to art school, which, if I had known then how hard it is to make a living as an artist, I would've maybe chose something different.

Miranda Metcalf Really? Gonna be a chemical engineer or something?

Aaron Coleman Yeah, why not? I get mad at my parents all the time. I'm like, 'What were you thinking when you decided it was okay for me to go to art school?'

Miranda Metcalf You know, it's funny, I kind of feel that way. I have those same sort of thoughts sometimes where I'm like - you know, my parents were always like, 'Just do what you want and the money will come, and you know, follow your heart.' And now that I'm like, 34, and only have like, $1500 in savings, I'm like, 'You lied to me!' But then again, I also love where I am and what I do and our community and all of that. But yeah, I've had similar thoughts of like, Goddamn fucking supportive hippie '60s parents!

Aaron Coleman Yeah, man. You know, my mother's a government employee, my father was a procurement lawyer. And I'm just like, 'What were you thinking?' And I know it's not their fault. And I'm happy. I like what I do. But I definitely could be financially better off. That's for sure.

Miranda Metcalf Tell me how you came to printmaking.

Aaron Coleman It's probably kind of a boilerplate answer, maybe, but I thought graphic design, okay, this makes sense. You know, coming from graffiti background, writing words and text on things. I'll try graphic design. I did not like being told how to make an idea better. It's not that I didn't like being told how to make an idea better, I didn't like being told that 10 times in a row. So you make a design for an advertisement, and then it gets kicked back to you. And they say, 'Well, can you move this here and push this up here and make this this color instead of that color?' And you say, 'Sure.' Then you do it again, and then they say, 'Okay, now can you move this and do that and do this thing?' And you say 'Okay, sure.' Then you get it back a third time, and they're like, 'Okay, how about this,' and before you know it, it's not your design anymore. So that got really annoying to me and I switched to painting, but I'm not a good painter. It's funny, because I have tremendous patience with printmaking, but I don't have any patience for painting. So I end up with these swampy, mushy, brown canvases within like five minutes because I tried to put all the color on the painting at the same time. And I had a painting professor who told me that he was going to give me a D, and he said, 'I should fail you. But I don't ever want to see you again.' So I was like, maybe this isn't for me. So I took a printmaking class. And you know, I think most printmakers, the thing that really draws us in is the community. You know, you talk about keeling over on a press. And the thing is, everybody in the shop has to use that press. Everybody has to use the stones, everybody has to use the acid bath. And these are things that are too expensive or too dangerous or too heavy to have in your own home studio, like everything you need to make a print, isn't really available to everyone. And so printmaking revolves around these community spaces where a lot of people can come and use equipment and materials and chemicals in a group setting. And so I think that sense of community just kind of is contagious, and it caught me immediately.

Miranda Metcalf And where were you for your undergrad?

Aaron Coleman I was at Herron School of Art and Design in Indianapolis. So some folks may know David Morrison, who's kind of a virtuoso, but an incredible lithographer, meticulous lithographer. And Meredith Setser is there, she makes really amazing work on felt, she's like handmaking felt and printing etchings and screen prints and relief prints on felt and then making these immersive installations. And Andrew Winship is there. So I had some good mentors there.

Miranda Metcalf I would say that one of the things that you're known for is your really beautiful lithography. So it sounds like you've had some really good introduction there. And then -

Aaron Coleman Not really, though.

Miranda Metcalf Not really? Oh, okay.

Aaron Coleman That would make sense, like, A to B to C would be the logical train of thought, but it was more like A to X back to B again. I was there seven, I was an undergrad for seven years. I was at Herron for four years. And I didn't work with David Morrison until my last year there. And so I had been working in printmaking for four years already. And I hadn't really made any lithographs. But I was working in lithography that last year, and David Morrison came up behind me, and you have to remember, I've only known him for a few weeks at this point. And he kind of slaps me on the back with his giant bear paw hand, and he says, 'Well, Coleman, we might make a printmaker out of you yet.' And I thought, What do you mean? I've been making prints this whole time I've been here. But apparently, I had just made something worth a compliment.

Miranda Metcalf Gotcha. So then from from there, though, you went to grad school, and you worked with Michael Barnes, is that correct?

Aaron Coleman Yeah, he was at Northern Illinois University. And David Morrison, my last semester there, said, 'You need to go study with Michael Barnes.' And I said, 'Who's that?' And he looked at me like I was an idiot. And then I got to grad school. And Mike is an amazing human being. He's one of the most caring mentors I've ever had. He's hilarious. He has a temper. He's just a really dynamic, amazing individual. And he's kind of the opposite, when it comes to lithography, as David Morrison, he's like the opposite of him. So where David Morrison would have me etching my stone with six different etches and six different paint brushes, Michael Barnes would just throw one etch on the whole stone and rub it around for a minute and say, 'Okay, you're good to go.' It was really opposite perspectives. So now I kind of work in between the two, I think.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah. And how was grad school for you? Did you find it like a really productive time, or intimidating time, or fun?

Aaron Coleman I wouldn't say it was intimidating. It wasn't intimidating, not because I think I'm good at what I do, but because I'm kind of oblivious to shit like that. Like, I'll just walk into a situation and not really pay attention to what's going on. I'm just there to do a thing. And so I went to grad school, and I was there to do a thing, which was make stuff and get out. And so whether I was good or not didn't cross my mind. So I wasn't really intimidated, until I had my first critique with Mike. And we all had our work up on the wall. And I was talking for about five minutes about the work I was making. And he, from the back of the room, said, 'This is boring.' I was like, 'Uhh, okay.' And he was like, 'You're not in this work at all. I don't see you in this work. What do you care about?' And so that pissed me off, kind of, but then also, maybe it was my first understanding of what grad school was and why I was there. And every critique after that was bad. Mike once told me that my work was "contrived and predictable." Ashley Nason was a printmaking professor there at the time, and she told me that my work looked like it "belonged in a head shop." So I got beat up a lot while I was there, and my work changed a lot. And we were in DeKalb, Illinois, which is about an hour and a half outside of Chicago. So it's kind of just out of reach of the city. And so I spent a lot of time in DeKalb, with my head down, making work because I didn't feel like commuting to the city. So coming out of those rough critiques, I just made work. I made a ton of work. And it wasn't until my last semester there that Mike kind of, he finally liked what I was making, he came over to me and he said, 'There's a job position opening at Southern Illinois University, and it's a lithographer position, and you need to apply for it. But that means you have to make some lithographs.' And I think he was kind of trying to trick me into making lithographs. Because I hadn't really made any since I had been in grad school. And so my last semester, I started making these lithographs. And that is kind of the work that most people know me for right now.

Miranda Metcalf So really, it wasn't like litho was your was your lady love from go, it sounds like you had a couple of mentors who kind of were a little bit forcibly moving your hand that way.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, people refer to me as a lithographer a lot. And they're not wrong. I do make lithographs. But I went all the way through undergrad having not made a lithograph until my last semester. And then I went all the way through grad school having not made a lithograph until my last semester. And so I had these big chunks of time with no lithography experience until the very end of working with a specific mentor, and they kind of just pushed me in that direction.

Miranda Metcalf And so then how did it become such a prominent part of your practice? You know, even after you didn't have to do it to apply for a job or you didn't have to do it from these other reasons, did you then just find that you did have a genuine connection with it? Or are you one of the people who just loves drawing? What is it about lithography that makes it so consistent in what you do?

Aaron Coleman There's a lot of things. I do love drawing, but I don't really consider what I do drawing. So maybe, I don't know, that might be another whole nother conversation. But I think what I like most about lithography is the versatility. You can make a reductive lithograph, you can make an additive lithograph, you can make a photolithograph, you can do all kinds of transfer methods. Lithography has this ability to weave in and out of painting and drawing and printmaking and the digital and a facsimile. I mean, it's so versatile. And I think that's really what connects me to it is this ability to make a lithograph look like a screen print, or to make it look like an etching, or to make it look like a woodcut. You know, you can do whatever you want to a stone. And it's not as easy to do whatever you want to, say, a woodcut or a screenprint. Intaglio is pretty flexible. But if anybody were to look at the work that I make, they would see a lot of lithography, but they'd also see all of these other processes that weave in and out, and they'd see me trying to make lithography look like other processes. So yeah, I think the versatility is what really draws me to it.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, definitely. I think that's a really apt way to describe part of your aesthetic is, especially when you see it just in reproduction online, you'll look at one of your prints and you'll say, 'Okay, is this screenprint? Or is this a lithograph? Or is this a mezzotint?' And the answer might be, 'Well, yeah.' But it could also be that even within that, it can be difficult to see what is what, I think. Again, particularly in reproduction, when you're not getting the textures that you can get in person.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, I mean, sometimes people ask, 'Well, what is this?' And the answer is simply, 'This is a lithograph.' And then there are other times where the answer is, 'Well, this is mezzotint aquatint with a photolitho chine-colle,' and they're like, 'What are you talking about?' And, you know, I think part of what I really like about printmaking is the ability to disguise the medium. Like, paint really exposes itself as a material. And that's not a bad thing, or a good thing, in my opinion. I don't really care either way. But I make work that is political in nature. It borrows from things that already exist to talk about history and sociopolitical current events. And so for me, being able to hide the fact that something is a lithograph, or a screenprint, or a mezzotint, takes it away from being just this art thing that I made, and makes people question what it is they're looking at. Like, is this an artifact? Or is this something new? Is it a propaganda poster? They can't tell what they're looking at. And I like that. I like being able to disguise the medium.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, I'd love to talk a little bit more about your work specifically. And particularly when you were talking earlier about graffiti and that kind of borrowing and the remix thing and that kind of hip hop culture, it suddenly had a light bulb on for me, for what you do in your prints, where it's like, you might see a toga, and then you might see a comic book, and then you might see something from the Renaissance or early 20th century. And it really is very cleverly remixed into an image that is its own thing. Do you think that that does come from your early art roots? Or is this just something that is of interest to you, to be a part of a broader dialogue?

Aaron Coleman Yeah, it's it's definitely a direct influence from my interest in hip hop culture and graffiti culture. You know, when I give lectures, I talk a lot about how the first place where I felt comfortable was in the hip hop scene. And you know, I grew up biracial, black father, white mother, and so I've always felt a little bit out of place. I always felt like I was kind of in between worlds, and hip hop, it just ignores all of that, right? You might have a sitar playing against Clyde Stubblefield drums with a Doris Day vocal sample over it. You know what I mean? And it's like, all of a sudden you have all these cultures and genres of music and eras in history all blending together. So that was the first time I felt like I could exist between worlds confidently and not feel like I didn't belong somewhere, but that I might belong wherever I want to belong. And so that definitely impacts the way I see the world, the way I process the world, the things that I put into the world, the things that I create and then put out into the world, it influences all of that. And so when I start thinking about making work, the same way I thought when I was going to start making music, you know, I made music for about a decade, and I would listen and look and think about things around me and try to figure out how to use those things in my music. So those birds that you heard when I was outside earlier, I would be wondering how I could use those birds in a song. There was a time where I had a friend who lived in this old historic home. And in the basement, there was like a big empty oil drum, or some kind of big metal barrel, I don't know what it was for. And we used that as the bass drum in a song. We just went downstairs and banged on it and recorded that sound and used it as a bass drum. And so that same kind of pulling from the world around you is what I do in my visual work right now.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, and you know, while I'm pretty familiar with some of your work in recent years, and you've seen different time periods of imagery come up, you know, from sort of like stained glass to what your new body of work, which looks like maybe it's sort of like minstrel characters? Is that what I'm seeing in those?

Aaron Coleman Yeah, yeah.

Miranda Metcalf But the one thing that seems consistent through all of it, even when you're almost completely abstracted, is this kind of comic book aesthetic. So I'd love to hear you maybe talk about why that particular theme is so consistent in a practice such as yours that's so visually diverse.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, it didn't occur to me until recently that when I was a kid, my brother had figures from comic books pasted all over his bedroom wall. Like, he would cut them out of the comics and stick them to his bedroom wall. And that's really not significant in any way, it's just kind of weird. Because I inherited his comic books when I got older and he was gone. And I had all these comics with the heroes cut out of them. Which is kind of strange, it's a strange way to see a comic. And so maybe that planted some seed that I am just now realizing. But it really started when Mike Barnes told me that my work was boring. And he asked me, 'Where are you in this work?' You know, he wanted to know where my life was, where my experiences were. Because when I got to art school, all of that experience in the hip hop world, all of that experience in the graffiti world, just disappeared. You know, I left it all behind, for some reason, thinking that it wasn't valid experience, or it wasn't important experience, or important enough to talk about in the art world, or it wouldn't be taken seriously. And so when he asked me that question, it made me think about all the things that I was interested in before art school. And so text started to come back into the work as kind of a hangover from writing music and writing lyrics, and also from the graffiti world and painting text on walls. And then lowbrow culture started to find its way back into my work, you know, as a hangover from street art and graffiti. And so comics are this kind of lowbrow kind of cultural phenomena. And so that started to enter my work. And the very first comic book image I ever used was from The Death of Superman, where Doomsday defeats Superman. And in that book, Superman dies. And then there's The Return of Superman, where he's resurrected. And at the time, Obama was being reelected, or potentially being reelected. And there were all these religious extremists coming out of the woodwork and pushing all these political policies based on the Christian faith, you know, abortion laws, birth control, all kinds of things. But all of these things were founded in their beliefs as Christians. And so I thought, here we have Superman, who is this idealized figure who has been sent to Earth by his father to kind of take care of mankind. He dies, he's resurrected. You know, it's very similar to the story of Christianity, but no one's ever killed anybody over Superman. You know, we don't have the LGBTQ+ community being persecuted based in someone's beliefs in Superman. And so really, what struck me is that a lot of political policy and scientific study and social norms are structured around Christianity. And a painting of Christ is an illustration, in the same way that a painting of Superman is an illustration, right? They're both somebody's vision of what this figure looks like. But the belief system surrounding those figures couldn't be further away from each other on the spectrum. They're in a world of extremes, right? One is an entertainment, and one is a belief system that has caused a lot of joy in the world, but also a ton of pain. And so that comparison became extremely interesting to me.

Miranda Metcalf You know, I've never thought about Superman that way before, and now that you're saying it... Even some of that imagery, if I imagine that iconic image of Superman dead, and just even the way he's sort of lying - or is he being held even or something - I have this very clear image of him, you know, the torn outfit, and the limp body, and it looks like the descension from the cross.

Aaron Coleman Yes, exactly. So if you go to my website, there's a portfolio called Autophagy, and it's a series of digital prints that I made. And all I was doing was taking paintings of saints and religious icons, and finding comic book characters in the same exact pose, and superimposing them on top of each other. And there's a Caravaggio painting of Christ overlaid by a drawing of Superman, and they are in the exact same pose. And this happens over and over and over and over again. So if you're really curious, look at that body of work, and you'll see why those comparisons became so interesting to me.

Miranda Metcalf And I think that the early Christian stories, they are so much more about entertainment than we realize. Because it was like, they didn't have anything else. People didn't have something to talk about. There was no YouTube or Netflix or texting. You go home, let's say you're living in the Low Countries in 1490 and you go home after like working in a field or something, and you don't have anything. Except for, you have these Bible stories, particularly these Catholic, pre-reformation Bible stories. And even early wood cuts of saints, I can just imagine that they must have been traded the way a comic book might be, that it's sort of like, 'Oh, you have a St. Francis? I love St. Francis,' you know, 'I'll trade you for two St. Augustine's.'

Aaron Coleman Yeah, I mean, think about Zeus. I mean, there's always somebody that's willing to take advantage of something. And so the moment someone realized that Christianity could be used to make money or to enforce laws or to group certain people together or to exclude other people, it became a strategic construct. But when you think about someone like Zeus, that is a superhero, you know? It's this muscle bound guy hurling lightning bolts from the sky. It is. So you can only imagine if comic books had been developed in the 14th century, people would be believing in Superman. He would be the savior, you know? Yeah, I use comic books for that reason. And I use stained glass imagery for similar reasons. I think stained glass windows are kind of the graphic novel or the comic book of the religious world. You have big, bright, bold colors, heavy black outlines, simplified forms, idealized figures, stories of good and evil, morality. You know, all that kind of thing.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, I was raised in a very atheist house. But if ever I'm going by a church that's open, in a city really anywhere in the world, I'll want to go in to see the stained glass. Because it's just incredible. And it's funny how my husband who grew up really Catholic, you know, he'll humor me, but he'll be ready to leave pretty much as soon as we get in. I have this really, I guess it's sort of just lucky to be able to just have a pure aesthetic appreciation of them, and then also just a storytelling one. I'm like, 'Oh, man, yeah, that guy. Oh, man, it didn't end well for him, did it? Is he holding his own head?' I love that kind of stuff. And I didn't even learn about any of the mythology until I was in graduate school learning about the history of printmaking, and you had to learn that northern Renaissance. You have to learn a lot of biblical stories. And you're just like, 'These are so metal!'

Aaron Coleman Yeah, I mean, I grew up going to church. And when I was about 15, I said, 'Dad, I don't understand why I'm going here. I don't understand any of the stories, none of this resonates with me.' And he said, 'Okay, well, you don't have to go anymore.' And I said, 'Cool. Thanks.' And that was the end of it. But I always liked the way it looked. I always liked the way it sounded, you know, singing was always really impactful for me. The smell, the incense, was really incredible. So I mean, I have a kind of affinity for churches and cathedrals and things like that, and I seek them out when I travel. But you know, just the belief system behind it didn't ever quite resonate with me.

Miranda Metcalf And that's really great that you came from a family that just understood that faith is not something in any way that anyone, a child, a teenager, an adult, anyone, can be forced into.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, I meet a lot of people who see my work and think that I'm anti-religion, or anti-Christian, and I'm really not, I'm none of those things. I think if faith works for you, then it works for you. It's when someone's faith starts to impact the life of someone else that I get frustrated or angry. And that's a lot of what I make work about, is those kinds of issues.

Miranda Metcalf I've always thought it was funny when people get really angry about people who have faith, because in my mind, it's always been like, look, if you're like an atheist atheist, like those really hardcore atheists, and they're so mad about it, I'm like, look, if really nothing matters, if there's no universal truth, if there's no divine plan, if there's no spirit after death, and then eventually the sun is going to blow up and the earth is just going to return to a hunk of carbon, why do you give a shit? If these people are giving themselves some comfort and happiness by going to a pretty building once a week? It seems kind of counter to their message in a funny way.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, it's a world of extremes. You got one group on one side and one group on the other.

Miranda Metcalf And your work definitely - and your statement, you touched on a little bit - but you know, your artist statement particularly, it really gets into, the Earth is on the edge of environmental disaster, and we're just kind of in this shitstorm. And you know, as you mentioned, LGBTQ+ communities being persecuted, economic inequality, racial inequality, all of these things that are super... it always reminds me of that classic activist phrase, "if you're not angry, you're not paying attention." So all of this absolute shitstorm is going on around us in really scary ways. I'd love for you to talk a little bit about, where does art making fit into a world like this? Should we all put down our rollers and go be activists? Or where does making fit into that?

Aaron Coleman That could be a podcast in itself, that's another huge topic.

Miranda Metcalf Totally. Well, maybe we can have you back on for episode two, and we'll just deep dive into that one.

Aaron Coleman I mean, I'm constantly aware of the fact that I make political work, but I'm not throwing Molotov cocktails at cops. You know what I mean? I'm not on the front line of activism, so to speak. But I think activism and art, they both are like anything else, in that you need different people for different jobs, right? You have people in activism who are really good at speaking. And those are the people that you want with the megaphone in their hand. You have people who are really good at fundraising. And those are the people that you want on the phone making money for causes. And you have people who are really good at distilling all of these ideas and phrases and sentiments and issues into an image. And you never know when a piece of art is going to spark some interest in an issue where it wasn't existing before. If a group of students go on a field trip to a museum and they see a Theaster Gates firehose painting, they're going to wonder why this guy is making paintings using discarded or decommissioned fire hoses. And that's going to bring up the history of police using fire hoses on African Americans in Chicago. So it's like, one thing leads to another. And I really think we need all the different kinds of brains we can get in an activist society. And so we need people on the front line. We need people documenting, through visual culture, our history and our current times for future generations to look back and have an image of what was going on, and we need all different voices in this scenario. And so that's how I think visual culture fits in. I mean, even when you look at the Black Panthers, you know, they had their artists working, making images for each newspaper that they put out. Emory Douglas, he was a woodcut artist that made the imagery for the Black Panther newspaper. And so he put a voice and an image to very complex issues that maybe wouldn't have gotten across as quickly had you had to read an article about the issue. My father used to say "it takes all types." And that phrase is really meant to dispel discrimination and say, like, it takes all types of people to make the world go round. But I believe that really fits with kind of any cultural facet that existed. And if an activist society is that, then it takes all types, it takes the fundraisers and the speakers and the organizers and the aggressors and the pacifists and the artists.

Miranda Metcalf And I think what you're saying about the artists as documentarians is hugely significant. And something I never thought of before is that when you think about a movement like the Black Panther movement, and it's like, what do you think of? Well, it's usually, at least probably for me and you and other visually driven people, you're thinking of these iconic images. Like the posters, like the people who are doing the photography documentation, like anything in that visual realm. And the images that kind of float to the top of our consciousness do capture so much more than just whatever the first two lines on Wikipedia are about a movement.

Aaron Coleman I mean, if you say Black Panther, most people will think of a black fist in the air. They're not going to think of Huey P. Newton, because a lot of people don't know who Huey P. Newton is. But they know what a black fist in the sky means. And that is visual culture, right? That is a lasting bit of visual vocabulary that carries weight and meaning forever.

Miranda Metcalf I would think also, you have your practice as a teacher as well, and I think that that could be - again, maybe a much larger topic, but - I think that being an influence and being a resource and a support for people who are about to kind of enter the world as the next leaders - and that's a generalization, obviously, there are people who go back to school older - but for the most part, you're dealing with kids, and being an influence on them, that is a political and significantly influential part of helping the world, I would think.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, absolutely. And it's not as simple as one might think, and I don't mean teaching, I mean that kind of fostering of a culture, or a culture creator, or a political mind or something like that. It's not as straightforward as that, because I have to balance or move between different kinds of minds. And so I might have a student who is looking to voice their experiences as a queer brown person. And then I might have someone that comes from extreme privilege who wants to talk about the same issue, and trying to figure out and help them figure out the appropriate ways to talk about their experiences, or the things they care about, is a really difficult job. And so I teach pretty straightforward media and practices, you know, printmaking and collage and things like that. But a big part of my job is facilitating the most authentic voice I can for each student. Here, an hour away from the border, those conversations are often political in nature.

Miranda Metcalf That's interesting, because I'd kind of forgotten how close Tucson was until you just said that. Because I was there maybe 10 years ago. And of course, I remember sitting on my sofa, crying out of happiness with Obama's reelection. I remember, it was like, 'This is so amazing! We're doubling down on progress!' And then how that seems like a world away to the world that we're living in now, and particularly when it comes to border issues. And maybe not even particularly, it all seems like a fucking world away now. But that whole... border politics has become so hot and so charged and so sad and full of anger. And yeah, Tucson, it really is, it's right there.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, I mean, I have Hispanic students who are frustrated, and they want to talk about those issues. I have Hispanic students who want to be Hispanic artists and not be expected to talk about those issues. And of course, both students have the right to do each of those things. And so that is just kind of a snapshot of the role that I have to play as a teacher, in facilitating those kinds of conversations. I'm half black and half white, and one of the first things that I tell graduate students, African American graduate students that come to our school or to any school, is that you don't have to make work about being black. Just because you're black doesn't mean you have to make work about that. You can make work about whatever you want. And so I have to have that same conversation with Indigenous students and Hispanic students and white students and everybody.

Miranda Metcalf I can only imagine that being.... I assume you're one of only a handful of people of color on the staff, because that's the way it is in most any university in America, that's got to certainly affect the way that you're asked to perform as a professor, and then also the way the students see you and turn to you, particularly students of color.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, 100%. Any university you go to, you're probably going to find a lack of diverse faculty. And it's kind of a cyclical situation, it kind of perpetuates itself, because you have minority students going to a university and not seeing any professors or mentors that look like them. So they don't feel like they belong there. So they either don't go to school, or they don't continue on to graduate school. And even when they do continue on to graduate school, they may still not have a minority mentor. And so then they're not applying for the jobs. And so then the jobs are being taken by straight white men. And so it's a system that repeats itself. And so mainly, what I do, or what I try to do, is empower all my students, not just minority students, but everybody. I really want to instill in them that there is a place for their voice and what they do, so that they feel included, they feel like they belong there, so that they can move forward with everybody else. And like I said, it's not just minority students. It's minority, it's female, it's poor, it's queer. I mean, anybody who has been historically marginalized needs to feel like this world is for them as much as it is for anyone else.

Miranda Metcalf That is super important, and really beautiful. And I am so happy that you are a professor that students can interact with and get access to. It's just so important. And I think it speaks so strongly to that need for more voices, more life experiences, in positions of power and in positions of influence.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, absolutely.

Miranda Metcalf I think that's just gonna have to be a great note to end on, because the construction has started in my building. And so I don't want it to be distracting and kind of drown out what you're saying. But if you'd be open, I would love to have you back on sometime again. And we can do a deeper dive into some of these great topics that we were chatting about.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, anytime, of course.

Miranda Metcalf Excellent. Well, thank you so much for taking the time. I know it's a really busy time for you. But it's been a pleasure to chat about all the things.

Aaron Coleman Yeah, I totally agree. It was fun.

Miranda Metcalf Cool. All right. Talk to you soon. Well, that's my show for this week. Join me again in two weeks' time when my guest will be Marco Sanchez. And don't forget, it's going to be a special double release episode. One chat in English, the other in Spanish. This episode, like all episodes, was written and produced by me, Miranda Metcalf, with editing help by Timothy Pauszek and music by Joshua Webber. I'll see you in two weeks.