episode forty-five | carlos barberena

Published 27 May 2020

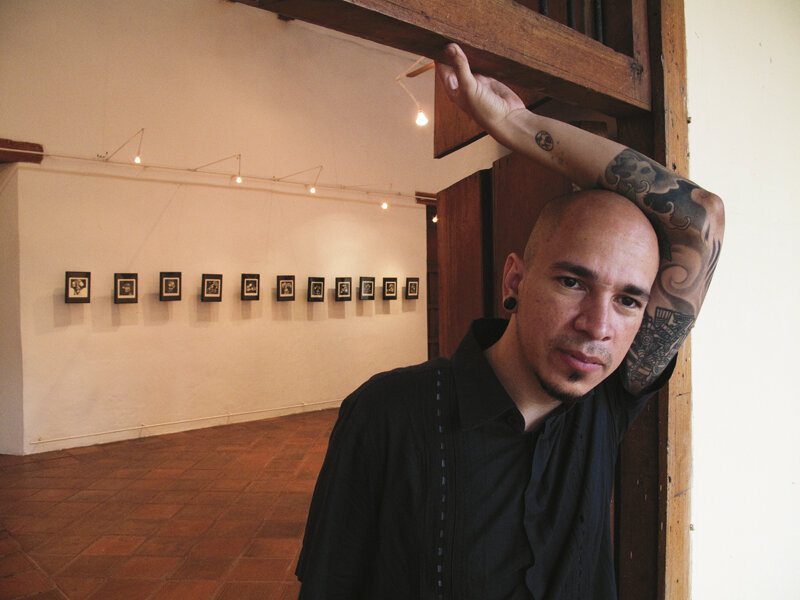

Photo by Glow Ruiz

episode forty-five | carlos barberena

In this episode Miranda speaks with Carlos Barberena, a self-taught Nicaraguan Printmaker now based in Chicago, where he runs Bandolero Press and La Calaca Press. Barberena grew up in the 1970s during a violent and volatile revolution. At a young age he fled over the border to Costa Rica where he and his brothers sought refugee status while they sold their drawings on the thoroughfares. Today he is well-known for his satirical relief prints which interweave the imagery of pop culture with that of political and cultural tragedies. This interview was recorded in mid-April 2020, right at the height of COVID panic and as well as his story, he also shares some beautiful insights into what we all can be doing now that the world has forced us to slow down.

Transcript

Miranda Metcalf 00:27

Hello print friends, and welcome to the 45th episode of Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend), the internet's number one printmaking podcast. I'm your host, Miranda Metcalf. I release weekly podcasts with people in the print world doing something a bit beyond the expected, so please subscribe on your podcast listening app of choice. You can find Pine Copper Lime on Patreon, Instagram, Facebook, and you can sign up for the monthly newsletter with print news from around the world, all found at helloprintfriend.com. Printmaking forever, shun the non believers. My guest this week is Carlos Barberena, a self-taught Nicaraguan printmaker now based in Chicago, where he runs the projects Bandolero Press and La Calaca Press. Carlos grew up in the 1970s during a violent and volatile revolution. At a young age, he fled over the border to Costa Rica, where he and his brothers sought refugee status while they sold their drawings on the thoroughfares. Today, he is well known for his satirical relief prints, which mix the imagery of pop culture with that of political and cultural tragedies. Carlos and I spoke in mid-April, right at the height of the COVID panic. And as well as his story, he also shares some beautiful insights into what we all can do now that the world has forced us to slow down. So without further ado, sit back, relax, and prepare to get political with Carlos Barberena. Hi, Carlos, how's it going?

Carlos Barberena 02:12

Hi, how are you Miranda? Well, I'm doing well.

Miranda Metcalf 02:16

Good, good. Yeah, I feel like that question has such kind of new overtones in our new world, when you ask someone how they're doing.

Carlos Barberena 02:27

At least I'm having good health. That is important right now. But you know, also sometimes it's overwhelming with everything that's going around, has been around.

Miranda Metcalf 02:40

Yeah, how have you been doing in quarantine yourself?

Carlos Barberena 02:45

Well, it has been a lot of things, you know, like, planning things before [everything was going down]. So I'm an artist in residence in a gallery in the neighborhood. So everything was shut down, and also, I was in the middle of moving my studio, setting up my studio in a house, because we moved to a new place. So just half of my studio isn't set up. So these kinds of things, like, I want to do some work, and oh, my plate is in another place. But at least it's like, I'm having more time to have some more revelations [about] what's going on. And I'm from Nicaragua, so I have family down there. And also, I check in, like, what's going on down there? Because it's like, the government is still in denial of what's going on, so they are not [doing] anything to prevent this pandemic. So it is kind of like a very hard time, I think.

Miranda Metcalf 04:08

Yeah, I think for a lot of people, because we live in a world where we're so separate from family, like, I live in a different country than my family, my family are in the States, and I'm in Australia. And it's like, you're so concerned for these people that you love, and you're so far from them. And it's just like, it doesn't make things easy, that's for sure. Yeah. Well, I'm really glad that we could find a chance to connect. I've admired your work, I feel like, for years. I can't even remember when I first came across it. I feel like it's just always kind of been a part of my understanding of the contemporary printmaking world. But for people who may not be familiar with you, would you mind giving yourself a little bit of an introduction, and just telling people who you are, and where you are, and what do you do?

Carlos Barberena 05:08

Yeah, thank you for this opportunity. Well, I'm originally from Nicaragua. I grew up in a family that has some tradition in the arts, my two older brothers are artists as well. So I grew up in this kind of environment. So when I was young, I had to leave my country because of a different situation, the Civil War, so I emigrated to Costa Rica. So I was there as a refugee. So for me, it was like a very hard starting point, to start doing art. Because it was the way that I could express myself [as] I was living during that time. And I was doing more paintings and drawings. And it was after I returned to Nicaragua that I started getting more interested in doing prints. But I never had the opportunity to work in a real print shop. It always was kind of like workshops and things like that. And I had the opportunity to go to Mexico, to a place called Pátzcuaro in Michoacán. So I was doing a residency there, and I learned more about printmaking. So it was in 2007 that I came the first time to the United States, like I just got to do my papers for my visa here. And I moved with my wife in 2008. And we were living in Seattle for a couple of months, and after that we moved to Chicago. So since 2008 I have been based in Chicago, and I had the opportunity to work in a print shop in Oak Park that is called Expression Graphics. So from there I had a lot of opportunities and I got to work and collaborate with different artists. So I went more into printmaking and I quit painting. So from there, I was like, 'I'm still doing prints.' And so when you were growing up in Nicaragua, you said that you had a bit of an artistic family and that your brothers are in the arts as well. Were your parents in the arts? Was this something that they really sort of fostered in your family, people making and consuming art? Yeah, well [on] my mother's side, there [are] a couple of painters, like one of her uncles was kind of like a famous painter. He studied in Germany, and mostly he was doing portraits and things. And there is another part of the family that [was] doing more contemporary art during the '70s. So for me, it was like a... you know, growing [up] in this family, my grandmother always hosted poetry studies, or musicians. So it's a lot of musicians and poets and artists like on the side of my mom's family. And my father used to write short stories, play guitar, and he did some watercolor. So it was a very... like, my mom was just pushing us to do more art. And when I was starting more drawing and things, it was during the time of the revolution in Nicaragua, so I went to one of those schools the revolution was promoting. And my mother said, like, 'Okay, we're gonna have another artist in the family.' Because my two brothers, they were already in the school. And it was kind of a tough experience. It was not enough for me. The instructor, he was so rude. It was like he was 10 years old. And I remember, he [told] me to draw a bottle, so I did kind of like a version of a bottle, but it was like Cubism. Because I was watching my brothers, they were in the school, and they were doing this kind of stuff. So that guy came and said, 'You don't have any talent! Why are you in here!' And he threw out my drawing, and I said, 'Never, never, never am I going to take up a pencil again!' You know? So it was very frustrating. And it wasn't until I left my country that I started drawing again. But it was, like, years after.

Miranda Metcalf 10:49

Yeah, I don't blame you.

Carlos Barberena 10:51

Yeah. And it was something kind of like... it was very organic, because one of my friends, he was taking drawing class with my brother. And we used to play baseball. And I was waiting for him, like, 'Hey, we're gonna go late to the game,' and everything. And while I was waiting, I started drawing again. And my brother said, 'Hey, those drawings are kind of interesting. You know, like, we could sell it.' And I was like, 'No way.' So one day when when I had, I think like 20 drawings, small drawings, he took me to this place that was kind of like souvenirs, you know, that was just [sold] for tourists in Costa Rica. So it was this woman, very, you know, serious, at a table, everybody made a line. And she was looking at everything. So it was my turn, and I put my drawings there, and she started looking and just [setting] apart drawings. And she put three on another side, and said, 'If you work more on these three, I could buy everything.' And I was like, 'What?'

Miranda Metcalf 12:24

Yeah. How old were you at this point?

Carlos Barberena 12:27

I was like 17, 18 years old.

Miranda Metcalf 12:29

Oh wow. So you were still just like a kid. Yeah.

Carlos Barberena 12:31

Yeah, it was like, I used to sell the work of my brother. Because my brother, it was too [hard] to sell his own work. And I remember, we used to go to the embassies, just looking for the cultural attachment of the embassy, and just go there, and we would start talking and everything [about how] we were immigrants, we were refugees, and everything, and I think mostly it was kind of like, people were looking at me like a kid, I remember, I was like 15 years old or something like that. And we were doing this just to survive, and just selling stuff on the streets, like in plazas and things like that. But I think it was very important to me, having this kind of experience. You learn a lot.

Miranda Metcalf 13:37

Absolutely. What kind of images were they? Were you drawing the baseball players in the field? Was it of what you saw? Were they just completely imagined things?

Carlos Barberena 13:49

No, it was just kind of like things that I remembered. And my first drawing, it was like India ink, like a very intricate drawing, and it was mostly, like, houses. But it was empty, like it was like a landscape and there wasn't any human being there. It was just adobe houses, the kind of houses that I grew up [in]. So it was like more nostalgic work. And after one day, I woke up, and [there were] all the acrylic sets of my brother, so [I decided], I'm gonna start painting. So it was like, I'm gonna try painting, but it was a very primitive kind of painting. So I was kind of not [yet understanding] perspective, composition, and things. But I was learning, so my brother was helping me. So I was kind of doing these kind of images of the immigrants, the farm workers that went to Costa Rica, just growing and harvesting the sugar cane, the coffee, and different things. So I was more focused on that, and also trying to know more about my roots, to explore more about indigenous people. And that was one of my things, my representation of my work during that time.

Miranda Metcalf 15:44

So you did come to printmaking, it sounds like, when you were in Chicago? Like you'd known of it, but you sort of found your way to it working at the print studio, is that correct?

Carlos Barberena 15:55

Yeah, it was like, before I had some opportunities, so I always was kind of [attracted] to printmaking, but I never tried it. Like, for example, in Costa Rica I met one of the great masters there, Francisco Amighetti, and we showed together, and we talked and everything, but I never like... tried to do a print. And it wasn't until, I think was in 2002, so in my hometown there is a cultural center. It was the house of this priest, there is a [priest who] just passed, Ernesto Cardenal. So he donated this house to another artist and actor from Austria. So during the turn of the revolution, they started working in the house. And they did kind of the investment in bringing in all the equipment. And one of the [people] that was involved, he was printmaker. And he brought a convertible press, a beautiful press, etching and litho, you can work both. And he was down there, one time that I was visiting my hometown, and he invited me to do some prints. I didn't have any idea about like - I knew what was the print, but I didn't know what was the process. And he was mostly working on etchings, aquatint and drypoint. So my first print was a drypoint. And it kind of got very interesting, because now I'm in love with relief print.

Miranda Metcalf 17:56

Yeah, definitely. And that's such a different feel, like, so graphic and bold, but yeah, drypoint is just the most delicate. Yeah.

Carlos Barberena 18:07

So after that experience, like a couple of years after, I did a show in my hometown. And it was this opportunity to go to Mexico. With the idea to work more, to study more etching, and coming back to this print shop and teach while I was learning in my month. So I went to Mexico, I was very [excited] about [going] there. But when I got there, they were on a strike, all of the people that were working there. But they didn't tell me until I was there, so it was like, I had lunch with the director and everything, and everything was fine. When I got to the print shop, I was looking for my plates and everything, to start working, you know? Just planning. And I found in my table two limestones. And I was like, 'What is this?'

Miranda Metcalf 19:24

Yeah, right?

Carlos Barberena 19:25

And I didn't have any idea how to work lithograph. So the only guy that was there was the printer, and he told me, 'Just draw!' But I was like, 'I was supposed to come to work and learn more about etchings.' And he said, 'No, you don't have any materials, and this is the only thing that we have.' And it was around, I don't know, it was like a Tuesday or something. And he said, 'And you have to work fast, because we have to do the edition by Friday.' And I was like, 'What? What's going on here?' But in the end it was kind of like, okay, that's fine. And I did it, and it was kind of frustrating, you know, because I was supposed to go there. And luckily, I met some people in Mexico City before going to Patzcuaro, and they let me stay at their apartment. So I was kind of just going around old Mexico City, just getting lost in the subway and everything. Just eating the food and everything, going in every museum. And one of the things that is very important to me that had a big impact in my work, in the way that decided... I was kind of just getting bored painting, but I think who pushed me into printmaking, it was Posada. So I went to the National Museum, and it was a big show of him. And it was my first time looking at Posadas. So I was so amazed about his work, about the satire in his work, and how he was doing - not only like... everybody just like knows about the skulls and everything. It's about his whole body of work. So he blew my mind. And when I returned to Nicaragua, I was talking with my brother, saying, 'We need to do something to change this.' Because in Nicaragua, the printmakers, they were thinking as a painter. It was more like a selfish thing. It was like a small circle, and they didn't teach you anything. And I was visiting this, my short residence in Mexico, it showed me how to share. How you have to work with other people. And normally, just working together, you start sharing ideas and helping each other. So when I came back to Nicaragua, I was very excited and tried to do so. So we started working together, and just started doing shows around, and just doing demonstrations, free demonstrations and everything, and then giving away prints and everything.

Miranda Metcalf 22:52

So when you returned to Nicaragua, and you were doing your printmaking, and doing the demonstrations, is printmaking pretty well known, or were you kind of introducing it for the first time to people?

Carlos Barberena 23:04

It doesn't have the same history like [it does in] Mexico. [There were] some printmakers, you know, working on the newspapers. And I have been doing some research there, and there were a few. One of the things that was like a big thing in printmaking was during the time of the revolution. So the first press for the School of Fine Art came in the late '70s. So it was during the Somoza's dictatorship. So the Somoza family ruled the country for 45 years until the revolutions. And that press was donated by the Organization of American States. And all the students, they started doing prints against Somoza, and he wasn't happy with that, you know. But after the revolution - so then the revolution happened in 1979 - so all the leftist artists started coming to Nicaragua to work in Nicaragua. And many Nicaraguan artists, they were going outside [of Nicaragua] to learn more about art. A lot of people went to Cuba, Venezuela, to the Soviet Union, Russia now. And it was a boom, because it was the way to spread the word in the revolution. So it was all kind of propaganda. So it was a lot of beautiful posters, like relief print and screenprint, about the revolution. So everything was an original, you know, it was printed. All the posters, and everything. So it was like the big boom in Nicaragua during the '80s. But you know, after we saw the problems during the revolution, the US embargo, the Contras supported by Reagan, and everything, you know, it was a lot of pressure on Nicaragua. The people that were in charge, they lost the election in the '90s. And the new government, they were more into neoliberalism. So everything was shooting down, and of course, the first thing is culture. So when the printmaking studios in the School of Fine Art were dying, in my hometown, these people that were coming from Germany and Austria started racing. It's always going up and down, the printmaking scene in Nicaragua. But I was very excited to come back from Mexico and start pushing. And when I moved in 2008 to Chicago, I was to start working more with people and collaborating, and I had the opportunity to participate in different portfolios. And I was like, 'Oh man, this is great!' Like, you can share this with other people. So I started organizing a print exchange. So I did a three print exchange, and I took it to Nicaragua to show, and I brought Nicaraguan printmakers to show different work, and also like sharing their work, and showing it here in the states and in other countries.

Miranda Metcalf 27:05

So when it comes to your own work, how did you sort of focus on getting better and honing your skills without that formal class situation through university? Did you watch videos, were you talking to other artists? How did you get to be such a skilled relief printmaker like you are now?

Carlos Barberena 27:26

It was a kind of mix. Like, having the opportunity to work at Expression Graphics, I had the time to share with other printmakers. There is a printmaker from Mexico that helped me a lot, Rene Arceo, he organized a portfolio, and he is well known here in Chicago. So I learned a lot from him and other artists there. And also, I took different workshops, just to learn more. But I think basically it was taking every opportunity that I had. For example, at Expression Graphics, it was working as a co-op, and you have to pay for using the press. And I was broke, so I was kind of looking for a way to have press time. And it was kind of working as a volunteer, running the gallery there, so it was like, if you sit in the gallery you can work in the print shop. And because it was very small and open, I had just one eye watching the door, and another carving or printing. So it kind of helped me a lot, and also I remember the first time I came to the states, it was in December in 2007, the first thing that I did with the money that I had was going to the [nearest mill] and buying a baby press. That was my whole goal. My father-in-law was kind of like, 'You're not gonna buy some paintings?' I spent all my money buying this small press, and you know, I was messing around with that. And it was the only thing that I was doing and I was into. And another beautiful thing was going to libraries here. Like, you could go and you could take their books home! That doesn't happen in Central America. So I would go take the books from the libraries, and just taking them with me and studying them at home. So that was the way.

Miranda Metcalf 30:06

Yeah, so it sounds like it's the combination of learning by just doing, and doing all the time, and then seeking out the resources like books and that kind of thing. And so, in terms of the actual content, the subject matter sort of focuses on these ideas of repression and resistance. And you're looking at things like Monsanto, to Palestine, to border politics. How did you come to focus on this?

Carlos Barberena 30:36

I think it is a combination of trying to express myself and going crazy with all the experience of life. So I grew up in Nicaragua, I was under the Somozas dictatorship. So it was one of the more horrible dictatorships in Latin America. So we went in Civil War. And then came the Nicaraguan revolution that was [led] by the Sandinista Guerillas. For many people, it was a big change. So there was a lot of hope in this revolution, that it was going to change everything, you know? And there were different things in the revolution, like free health care, like education, reforms in the farms, so giving land to the farmers to work on, and a lot of things. But [there were] different things that happened, and that revolution didn't work. Like, first it was embargo, the US embargo, and also because the Sandinistas, after they were leading the revolution, they turned more radical, part of the Sandinistas that took over after was more Marxist and communism. And [those] things affected a lot the way that Nicaragua could be changed. So it was kind of like, I just left and returned from school, and my mom said, 'You have to leave.' And I said, 'Why?' And it was like, 'No, you have to leave to Costa Rica.' And I was like, 'Why, why?' And it was because, during that time, it was the military service. One of my brothers were already in the military service. My older brother, he was already in exile. And they were calling my mom, just to put on some pressure. Because my older brother, he participated during the revolution, but after, in the turns that happened, he was disappointed and he left the country. And so it was like kind of like, they were like, 'If your son is not coming, we are taking all of your sons.' And I was 13 years old, so it was kind of insane. And the next day, I was on a bus and going to Costa Rica with my brothers. And it was kind of like, things like that, they can have a big impact. And also, living there in Costa Rica, I lived there as an undocumented [immigrant] for a while, before I could apply to the asylum or refugee status. And when I got the status, it was kind of like, you start to understand how people treat you. And you know, the media and everything [is] against all the immigrants, all the Nicaraguans, you are like the bad people. But it's the people that are growing your vegetables, your fruit, everything, for a miserable [amount of] money. So everything was just looking... so like, you know, when you are an artist, you just start meeting other artists. And it was like, all these kind of people from Chile, that came to Costa Rica as refugees during the Pinochet era. So everything you knew was just changing your mind, and having all these conversations with all these kinds of people, it was changing my mind. And also from my own experience. And it's kind of the things, like, just coming to the United States is like coming to the belly of the monster, you know? Like, all of the policies the United States have with Latin America. All this kind of dictatorship that the United States put in, and when it's bored, taking out. And all the pressure put to the countries. So it's kind of all those experiences, and after that revolution, Nicaragua was changing a lot. And during the '90s, with all the neoliberalism governments, changing more. So this gap [got] bigger between rich people and poor people. So we are, right now, the second poorest country in Latin America. So we are always competing, you know, who is the poorest? And we have a lot of research, it's just like, we haven't been lucky enough to have real leadership. So we have been trying right and left, and it didn't work. And it's kind of these experiences that I try to push in my work. Not taking any side, it's just like, taking the side of the people.

Miranda Metcalf 36:27

Yeah, absolutely.

Carlos Barberena 36:28

Recently, I was reading about, right now, the big irony, undocumented workers are essential. You know? That is insane. That is disgusting. Like, oh, so now you are saying that they are essential? It's like, between 50 and 75 percent of the farmworkers in the United States, they don't have documents. And now they have paper that says, 'Hey, you are essential. But it doesn't mean that I'm not going to deport you,' you know? So it's like disposable human beings.

Miranda Metcalf 37:17

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah.

Carlos Barberena 37:19

These kind of things I'm very interested in, because I have been in that position, you know?

Miranda Metcalf 37:27

Absolutely. When you're creating these images, it's really quite a variety of of different issues that your work addresses from all over the world, and I'm wondering how, when you're in it, and you're working on it, and you're kind of taking on all these really awful truths that are around all of us, how do you kind of keep from being overwhelmed by it? How do you keep up that energy of like, 'This is wrong, and I'm going to create an image that says that. It says how I feel, and then I can go over here, and I can create another one,' without just kind of burning out?

Carlos Barberena 38:07

Oh yeah, it's very difficult, you know. You don't have enough time to address everything that is going on. And one of the things that happened, like, three years ago... I was always working and working and working, and three years ago in Nicaragua, [there were some] protests. It was protests for elderly people, it was protesting about a new law that the Nicaraguan government was trying to put [into place], and it was just like, you have to be retired at 65 years old, and also it was kind of putting down 5% of what you were receiving. And also, it was retroactive, that law. So people that were already receiving money from the pension from their retirement, they were getting less money. So they were protesting, and the government, it is the same guy that it was during the '80s, during the revolutions. And he has been in power for almost 16 years, I think, right now. So they sent police to beat up the protesters, and also, they go to more hardship neighborhoods, and bring criminals and all these people that they know, to just beat up elderly people. So the university students jumped up in that protest, and the government started killing students. So it was a very, very terrible thing. And that was going on, and I couldn't work for months. I couldn't make. Like, to create something, I was just... everyday, I was on my computer, calling my family, 'What's going on?' Because it was just going crazy. It was like, they were burning buildings and taking students, and disappearing people, it was just something that hadn't happened in Nicaragua in forty years. It was a kind of dictatorship that we were living in before the revolution. So it was during that time of the revolution that you feel like, hey, they are different. But no, when they are in power, it's kind of like they don't care about it. And I think that is the time that I [felt] a lot of pressure.

Miranda Metcalf 41:10

And how do you find a way to kind of come out on the other side of it? Because you found a way to make work again. Is it just sort of time and processing it yourself that allows you to get to the point where you're ready to create work about what you were experiencing?

Carlos Barberena 41:29

Yeah, I think it took time to just think and reflect about what was going on, because I didn't want just to produce work and say something. I wanted to [be] thinking more and kind of taking more perspective, because it was like, first of all, I'm not down there. I don't know what's going on. It was like, the media was just ignoring [it, and there were] other people here in the United States, like Nicaraguans, with a lot of background, talking shit about it, like 'That is not happening down there, that is fake news,' and things like that. And it was very like, you don't know what's going on. So I was very careful, and it was more like I took the positions of people, you know? Like, I did a portrait of one of the students that was killed, it was a kid, at 15 years old. And for me, it was very hard, because it was a feeling that it was like me, when I fled my country. And this kid was in high school, and the only things that he wanted to do, he was going and helping the university students that were protesting. And he took the money that, every day, his parents were giving him to have a lunch at the school, and he went and bought some water. And when he was leaving the water, he was shot by a sniper. And there is no system more horrible, because the students took him to the hospital and they denied him medical attention because the government said if the students come in here, they don't have to receive any attention. And he died there. So it was these kind of strong things that I was having nightmares about, you know, how you can't do anything. And also people trolling you and everything. But I think also having work and also distractions that I do have when it's very tough for me to create something new is like, I teach classes. And I do collaborations with other artists. Like I work with a group of Latinx printmakers here in Chicago, we do a lot of educational programs and we organize a free festival in November that is called Grabadolandia, that translates to Print Land. And it's an event that we do at the National Museum of Mexican Art. And it's three days, it's for free, so we don't charge anything to the people. We don't charge to the print shops that we invite. We always try to invite an international printmaker to come, doing talks, and everything. So in some way, it's kind of a distraction for me, just going out and printing t-shirts and just getting the funds to have these events, you know. So I think doing different things is kind of taking out all the overwhelming... all my demons I have to deal with.

Miranda Metcalf 45:32

Right. Yeah, that makes sense, that the actual work can kind of exorcise the demons, or something, a little bit. That it feels like you're doing something, especially when you're so far away.

Carlos Barberena 45:46

The hard thing is just thinking of the end result of the work that you have to put out. And after the work is done, it's done. And you don't have to deal anymore with these kind of pressures. But when it's inside, in your mind, in your soul, revolving there, it's very hard.

Miranda Metcalf 46:13

Yeah. In terms of actually the imagery that you create, one of the things I wanted to ask you about was how you're dealing with some of these really heavy issues. But you'll often weave pop culture images into it. So you might see Mickey Mouse, for instance, appear in a print that is about something that is so grim, and I just am kind of curious if you could speak to that a little bit, in terms of how these pop culture images and icons kind of fit in to the message and why do they appear in your work and how you started using that?

Carlos Barberena 46:52

That is Posada's fault. I mean, it was kind of like, I was trying to do something more... kind of satire and things like that. I remember like, when I was doing paintings and I was approaching these kind of heavy things, I had a lot of criticism. Like, that my paintings were too heavy, these kind of things, like the galleries, they want more commercial, more something that they are going to sell. And I feel, you know, they are like, it's business, you know. But also, you have to have time to do this kind of work. And you want to express, to communicate. For me, kind of as an artist, I need it. I need to communicate something. I don't want to do something that is just decorative. That is not bad, if you want to do it, do it. And I have a lot of fun doing [artists calls] and things that are not heavy. That probably people like, galleries like, that kind of thing that is beautiful. But I was kind of trying to come up with something, and I was thinking about the way students at schools learn about masters, and are just copying them and learning. And I said, 'Okay, I'm gonna try something, but it's gonna be kind of a different thing,' you know. And I remember the first work that I did was the Venus by Botticelli. And it was for a show in Nicaragua that I got invited [to]. And I was thinking about it, and the show, the theme, was about Gaia. And one of the very interesting things, it was like, the people that were coming to the show, they were receiving a native tree. So you could go back after the show and just put it in your patio, or in your neighborhood, and it was a lot, almost 2000 native trees. So it was a big show that was funded by the Sweden Embassy. So I got invited, and I was thinking about, you know, Gaia, and how to put it right now, and how Botticelli was thinking and living during this time. And it was kind of like, in the back of your mind is some image, and you start looking. And I think it was like, some friend sent me a postcard from Italy or something. So I have the postcard right there, and I started looking and it was one of the angels blowing, and I was thinking, oh, this image could be very good for appropriating this image. And I could do some new work and put in all these heavy things, like instead of blowing air, the angel is blowing fire. And a mushroom [cloud] in the back, the Venus with the gas mask, and all these pipelines and everything. So I was trying to take this image, to appropriate that image with the same kind of composition, but also put in some more contemporary imagery there and create a new work. But also, using kind of a hook, because everybody knows the Venus. So people are going to come, and when they are close, they start looking at all these kind of things to have this conversation with the public. And they start thinking about, like, why this? And some people feel insulted, because I'm appropriating this. And you know, in the history of art, you have a lot of masterpieces that were appropriation of another [work].

Miranda Metcalf 51:31

Absolutely. Yeah.

Carlos Barberena 51:31

And everybody has, you know, references, and... I mean, it's just contemporary work. But it was kind of a strategy more, because if I create something that was going to be very dark and [going there]... nobody pays too much attention, but it's the hook, you know, to take it. And [there were] some things that were just looking at stuff and reading stuff... I created another, La McMona, I was reading a blog, and it was an interview with the director of The Louvre, about his position of putting a McDonald's in The Louvre. So the journalist was asking, why McDonald's? You know, it's France. And he said, 'Oh, it's perfect, because McDonald's is the icon in contemporary culture. And the Mona Lisa is the best representation of art.' You know? And I was like, 'Oh! I have to do a print!' And it was near to a show that was like a day of the dead show. And also, you know, with all the kind of experience of corporations and things like that... and you can see in my prints a lot of, like, the golden arches there... and it's far more like the contemporary landscape. Like I remember when I was traveling to another state for a show or whatever, and taking the train. So you can see, during the night, the McDonald's sign there. And it was [becoming] the landscape. And it's also, in Latin America, it's kind of a representation of capitalism.

Miranda Metcalf 53:45

Yeah. And particularly the brands, they become such shorthand. You know, you get an image that you can use, like the golden arches, that just comes pre-loaded with association for people, both positive and negative. And so when you pop it into your work, it seems like it's a great way to message a whole bunch of different concepts with just a few lines, which is really fascinating.

Carlos Barberena 54:13

Yeah, and I think it's more behind, because... it's kind of like my only experience, I remember when I was a kid, there was only one McDonald's in Nicaragua. And I went one time with one of my uncles over there. And during the revolution, because of everything that went down, McDonald's left the country, you know. But came [back] in the late 2000s, I think, or late '90s. And it was a huge line. It was like a three block [long] line to get into the restaurant. And it was like, why, people? Why? And during that time, people, families down there, they lived with $1. And I was like, why, why? Why are you gonna spend $5 to go for trash food? You know, you have amazing food that you could get. But it's the status quo. And I have a self portrait that is called McShitter. And it was when I was living in Costa Rica, so I was in high school there, and all my friends were going to the McDonald's. I think during that time, there were two McDonald's. But it was kind of a representation of the status quo, you know. And also where my friends were around. And it was so crazy, because every time that I was getting a hamburger or whatever, I got sick. But I [kept] coming back, because my friends were there, you know? And everybody was hanging out there. And it was cool to be part of that culture. Costa Rica is a very Americanized country. But after, like, in the States, I was invited by Melanie Yazzie to participate in a portfolio. And it was about American food, and I was like, 'I have to do something that is not something that people expect.' Like when you see like a criticism of American food that is not just putting someone obese, or something more obvious, you know. And I was like, 'Oh, I'm gonna do a self portrait,' you know. Put me in the spot, because I'm part of the problem too. I'm part of this society of consumerism. And it's like, you have to acknowledge that you are part of the problem to start changing something. So it's kind of like, you know, one thing is taken to another. So when I started this series, I was just coming up with different ideas. And I saw people, how they were attracted, and it was better feedback to my work than before. Before, I did a portfolio that is called "Años de Miedo," "Years of Fear." And it was kind of like, oh, it's very sad, it's very strong, you know. And it was kind of a part of a project that I wanted to do about the Civil War in Nicaragua. It was something that I did, like, in 2000. I did some big paintings, and I was hoping to move around in all Central America, all these countries that were devastated by the war during the '80s, '70s. But it didn't work. I didn't have the money, I didn't have the research to move it around. And so I decided to do a portfolio, a small portfolio. And during that time, I had a lot of reference from Guayasamin, [who] is kind of like a very cubist, expressionist artist from Ecuador. Kathe Kollwitz, Picasso, Goya, you know. And they were very dark and the way that I cut them was kind of like German Expressionism. So it was directly to the plate, no drawing, no nothing. Maybe just a couple of lines, but I was drawing with the tool. And people who saw it [were] like, 'Oh, he's so depressed.' You know. I remember, I was in an article, because I presented them the first time in Expression Graphics in Oak Park. And the article, it was like, "Nicaraguan artist brings the war to Oak Park," and I was like, 'What?'

Miranda Metcalf 59:30

Well, as we're kind of coming to the end of the recording time that we have, I'd love for you to tell people anything that you're looking forward to, anything that might be on the horizon. I know a lot of artists have experienced all of these things kind of drying up in the COVID era, because we live so much in the future, you know, looking for the next exhibition or the next conference or the next portfolio, but I'm hoping you can tell us anything art related, I guess, or not, that you're looking forward to that we can see sometime in the future.

Carlos Barberena 1:00:07

One of the things before everything hit the fan, so I was kind of putting together my studio to have a space to work more, we have been always living in apartments, and I didn't have a... I was working at a table in the living room, or if we got lucky, there was an extra bedroom and I'd have my studio in there. And now we have a space, we have a house, so we recently moved in January. So it was mostly working in the house, doing that kind of thing. So my year this year was more focused on just putting together my own stuff. I didn't sign up for any shows, like probably I'm gonna be doing shows, but now I don't know. But last year it was amazing, I was showing everywhere, I had a show that I put together like 80 pieces that I was so happy to see together at the show, and traveling a lot and having a lot of opportunities, but I was like, this year I want to just focus on me, just to get inside, get alone. I think I spoke too loud! And just start working on a new body of work and going in a different direction, and experimenting more. And that was my goal for this year, and was more like... what can I say? Just to rethink about what I have been doing during the last 10 years doing printmaking. And I think that is very important, to just stop sometimes and just to review what you have been doing. And, you know, I was just planning things with the place that I'm an artist in residence, just to keep [being a part of that] community and things like that. But now we don't know what's going on with big plans. But I think, I have been doing for years, these things... like right now, I haven't been able to print too much, so I have just been drawing and just experimenting with things.

Miranda Metcalf 1:03:22

Yeah, it sounds like [you're] kind of using the time as a bit for reflection and moving forward with intention, which I think is always good.

Carlos Barberena 1:03:32

And it's not only a part of the art. It's like, how we are going to resolve all these problems that we have been seeing? That are for real? All the insane things that is going to happen, that you can see? Like here in Chicago, the nurses are using plastic bags and things like that. They don't have the equipment. So it's horrible. Or just like the people that are more affected are Black and Latino people, you know?

Miranda Metcalf 1:04:09

Absolutely.

Carlos Barberena 1:04:10

Because they are more vulnerable communities. So what are we going to do change this kind of thing? And it's insane. It's very depressing, but at the same time, we need to work more. And I think we need to work more on the ground. I have no interest in the president, who is going to be the next president. It's not going to change anything. And it's more like working here, on the ground, with the people. So I mean, I'm disappointed with the way that it's gonna go with the elections, but we'll see what happens.

Miranda Metcalf 1:04:58

Well, actually, I think that's a nice place to wrap up. Because it, I feel like, really speaks so well about your work. This idea of, we need not to focus on continuing this cycle of the large forms of corruption that don't change anything. But to actually look to what we can change, which is, as you said, the grassroots. That is where an individual can actually affect things. So I think that that's a really beautiful place to end on. Can you let people know where they can find you and follow your work and see what's coming up on the horizon?

Carlos Barberena 1:05:47

Yeah, you can follow me Instagram, it's @carlosbarberena. I know it's sometimes very difficult with my last name. Also, I have a website with the same name, but that one is not always updated. So we're going to try, now that I have some time to work on it, but you can look at more of my work, and it's a more updated website, at bandoleropress.com. So it's gonna be more updated, and probably in the future, we're gonna be launching some projects. So kind of doing more interesting things.

Miranda Metcalf 1:06:38

Well, I can put links to your website and your Instagram and Bandolero Press all in the show notes. And thank you so much for joining me. This has been an incredible conversation, and I learned so much. So thank you again, this has been a real pleasure.

Carlos Barberena 1:06:59

Well, thank you so much for the invitation. I was very excited when I was looking, and I saw the other day, Martin [Mazzoura], because I know Martin, and also I saw another homie, Joseph Velasquez.

Miranda Metcalf 1:07:16

Oh, he's great. Yeah. He was a great guest as well. Well, I'll be in touch, and I look forward to releasing this sometime in the next couple of weeks. And I'll let you know.

Carlos Barberena 1:07:28

Okay, sounds great.

Miranda Metcalf 1:07:30

Okay, thank you so much, Carlos. Have a great evening.

Carlos Barberena 1:07:34

You too, and take care. Be safe.

Miranda Metcalf 1:07:38

Well, that's our show for this week. Join me again next week when my guest will be Jason Phu. Jason grew up in Sydney, Australia, the son of Chinese immigrants, and he creates playful and darkly humorous works which examine cross cultural communications, how we remember the past, and sometimes shitting yourself from drinking. You won't want to miss it. This episode, like all episodes, was written and produced by me, Miranda Metcalf, with editing help from Timothy Pauszek and music by Joshua Webber. I'll see you next week.