episode twelve | patrick wagner

Published 17 April 2019

episode twelve | patrick wagner

In this episode Miranda speaks with Patrick Wagner of Black Heart Press. Patrick is a lithographer, teacher, and sauna enthusiast from Germany living in Stockholm. We talk about his early days learning lithography from Alois Senefelder's treatise while at a small art school in Romania and the guerrilla litho teaching group it spawned which eventually got him kicked out of school. As well as the beautiful international connections the sharing of printmaking knowledge brings and the devastating fire which destroyed his entire archive of work. Patrick has an incredible deadpan humor which makes this episode a particularly delightful listen.

Miranda Metcalf Hello print friends, and welcome to Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend), the internet's number one printmaking podcast. I'm your host, Miranda Metcalf. I release an episode every two weeks, and on the off weeks, I publish an article on the Pine Copper Lime website, which features images and maybe a bit more information about the artist I'm going to interview. This week, my guest is Patrick Wagner of Black Heart Press, and oh boy, I envy you that you are about to get to hear this interview for the first time. This is a fun one. I mean, sure, we talk about dances of death and looming environmental catastrophes and the end of the universe, and not to mention a devastating fire that destroyed his entire archive of all the work he'd ever created ever. But trust me, Patrick is 100% a good time. And despite the at times heavy content, the main theme that runs through this whole episode is the incredible connections that printmakers create around the world over a shared passion and the lengths we go to to share knowledge and build community. Patrick takes us from Japan to Switzerland to Nigeria and back to a hole in the ice in Stockholm. We also get into the Art Sauna project. While not directly related to printmaking, technically, I do have a huge conceptual and logistical crush on it, and it's a really interesting study in human connections, and one might even be so bold as to say, relational aesthetics. The icing on the cake for this episode is Patrick's voice, which is probably one of the most relaxing things you've ever heard. I don't know. Maybe it's all the saunas. Just a quick reminder, before we dive in, the best way to get in touch with Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend) is through my website at helloprintfriend.com, or my Instagram, which is @helloprintfriend. I also have a Patreon up now. And if you haven't at least gone to the page to check out the video that I made for it, you really should. It's probably one of the funniest things ever created. And by created, I mean stumbled into. You'll just have to watch it and see. Make sure you stick through the end. It's only about a minute and 20 seconds, which I know is about 46 minutes in internet time, but trust me, it's worth it. And as always, there's a link in the show notes. And if Patreon is not your thing, hey, I get it. But it would really help me out if you left a review on your podcast app of choice or maybe told a printmaker or two that Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend) is out there and looking for more listeners. Alright. Without further ado, here's Patrick. Hi, Patrick. How's it going?

Patrick Wagner Hi, how are you?

Miranda Metcalf I'm good. I'm good. Thanks for joining me.

Patrick Wagner Yeah, thank you for having me.

Miranda Metcalf So I have been following your work and all your projects as I can get my head around them on Instagram for some time. I'm really curious about what you do and your background and that kind of thing, and how it's sort of intertwined. So would you mind just giving yourself a little introduction.

Patrick Wagner So usually, I say my name is Patrick, but actually, that's not true. My name is Patrick [with the German pronunciation], Patrick Wagner. I'm a German printmaker, and I live in Sweden since the last four years. I was always interested in prints, I suppose. But I lived next to a printmaking museum while I was studying English for about five years, and I sort of went there monthly. It's the Horst Janssen Museum in Oldenburg, Germany. Horst Janssen is one of the late great German printmakers. You don't have to agree with his persona so much, or his works, but somehow, that was the right time for me. And I literally lived next door in the theater market. So I went there once a month. And after five years of studying English, I was like, 'Okay, I need to drop out and go to art school and learn printmaking.' And that's what I did, enrolled in art school. Got in in a really small school in northern Germany, Muthesius Kunsthochschule in Kiel. I think they had like, you weren't allowed to go to the print shop for the first year or something, you had to do like a foundation year or something. But you know, rules are sort of arbitrary at times. So I just went there anyway, first week, and I was like, 'I need to learn printmaking because I lived next to the Horst Janssen Museum for five years.' And it turned out that the master printer or the guy running the print shop, Dietmar Hagedorn, was a huge fan of Horst Janssen and he's a big person, so he just lurched forward into this bear hug and was like, 'You've come to the right place, son -' you know, like, he didn't say that, but it was like, he conveyed that. He was like, 'Yeah, come on in, let's get started.' And that was my official welcome into the world of printmaking was this hug, which I'm still terrified of and fondly remember at the same time. And it just kind of went on from there into where it is now. To sort of round us out, for the last five years, I've been teaching lithography at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm. That's the reason why I moved to Sweden. And they've, this December, December 2018, they've decided to, I suppose they would like to say it's on hiatus. To me, it's like they've closed the shops and let me go. So yeah, I'm looking, if anyone listening to this needs a printmaker, hire me.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, you heard it here first. Yeah.

Patrick Wagner Right. So yeah, that's where I've been and that's where I still am based, in Sweden.

Miranda Metcalf And so was lithography your main focus in school as well, or how did you come to the most alchemy of printmaking?

Patrick Wagner Don't hate me, but it's actually, I love etching the most, it's just, it's the nicest. No, that was the shop, the shop in Germany was was an intaglio shop. It's kind of cheesy, but it's got all the alchemy parts, right? It's like, it smells of tar and varnish and turpentine. And it's kind of cool. And you get to hold the flame under your plate and melt on asphaltum or rosin or whatever. And I was just like, yeah, this is it. So I don't think I started with lithography before Romania. I went on exchange in 2008 to study in Bucharest, Romania, because they'd just joined the European Union in 2007. And so it was possible for me to transfer there as an exchange student and that year, they had two new students, one from Italy, and one from Germany, me. And they had a litho shop, but no teaching. So it kind of ended up with me reading Senefelder's instructions from the library, because they had a German book on it, which they wouldn't give out. So I had to like, copy it, and then go to the shop. And there was a group of students that was into experimenting, so I tried to make some lithos. And then I had a friend from Minnesota back then, I think he was working at Highpoint at the time, super generous with his time and sending me long email explanations that make perfect sense when you know what you're doing, and that are really abstract when you've never made lithography before. Like, buff in a thin layer of gum, you know, what does that mean? When you see someone it's so easy, and when you try to figure this out from an email, you're like, 'Okay, I don't know what "buff" is. I don't know what that word means. Let's just do some things to gum. Let's make it thin, however that works.' And from that, I was always interested in, how do you teach? And how do you communicate this skill? Because with everything, if you know, if you've done it, it looks super easy. How do you tell that to others that don't have this ease in their hands yet or something? So that was quite nice. That kind of started this little teaching group for my litho sort of experiments to share with the students. And that eventually got me kicked out of the school.

Miranda Metcalf Oh, no, really?

Patrick Wagner Yeah, you weren't supposed to pass on knowledge like that. And it's true, they were like, 'You can't do this anymore.' It was really fun, a really good time. I'm not not bashing the people or the school, but they also didn't make it easy. And that was kind of, I was like, 'Okay, good. It's good when it's safe and nice and welcoming environments that you're in.' And I think that's something that I carried later into my teaching. It's pointless to be hoarding knowledge and not passing it.

Miranda Metcalf Well, I feel like there's a little bit of that knowledge hoarding tradition in printmaking, going back into the history of people, you know, back when it was sort of a science full of this proprietary knowledge, that certain people, if you knew how to do something, you would have that edge above the rest. But I think for the most part, we've evolved beyond that and it's it's really nice, it seems to be such an open community.

Patrick Wagner I think for me, this was, like I said, this initial hug of, in this case, one person, but it's also the community, because I seem to spend way too much time in front of my computer just looking at printmaking stuff. And that led to reaching out to a couple of people. I remember, there's this Japanese guy that was uploading this 33 part series on how he processes and rolls up and etches a stone. And this guy was called Itazu Litho -

Miranda Metcalf I know him, I actually got to meet him and see his studio once. He's incredible.

Patrick Wagner Yeah, he's amazing. So I think like, 10 years ago, I sent him an email, you know, based on these YouTube videos, or something. I was like, 'This is amazing. This is so cool. Thank you for putting this out. Because I'm just teaching myself, I had no idea.' And he was super generous, he replied, you know, he didn't hoard his knowledge. First of all, he went through the trouble, right, he knows perfectly well how to etch a stone, but he went through the trouble to make these videos, to produce them, to set up the camera, to do all this work. It's way more work when you also have a camera standing there. And then he gets these random emails from these German people. And he said "guten tag!" Because he knows like three words of German. And suddenly, you have a friend in Japan. And they're sharing, and I've been at his place now, three times, I think, because he's teaching or he has been, I'm not sure if he still is, the last years he's been teaching at Geidai Tokyo. That's probably where you've met him, or that's where most people visit him, in the shop in Ueno. And it's amazing that there is this sharing kind of going on. And that led to me making my Black Heart Press Instagram, and before that, the Tumblr, which is still there. But yeah, there's always content being put out. And I was like, 'Okay, I need to do this, too. I want to do this too. As soon as I have something worthy to tell, or to show, I'd like to take the effort, take the time to put it out there again.' Mostly because I'm doing the research anyway, you know, if I look up some prints in some collection, I might as well just post about them. As a memory to myself, but also as a reference for others that might stumble across it and be like, 'Oh, yeah, that's cool. Look, there's this person that does these things,' or something, and if you've done the work, you might as well just let others benefit from it, I feel. And I think there's also something to be said for, no matter how well you think you know something, teaching it and breaking it down for someone else, you learn it from a different angle in a way that can be super beneficial too. So I think it benefits the teacher and the student. Yeah, or to see how things are done different in different places. Because I think we all know, everyone who's learned printmaking learned it one way, from the people that you had access to at that time were doing it. And so you're kind of like, 'Okay, this is the holy way to do it. You've gotta do this, and you've gotta do that.' And you go to another shop, and people are like, 'Sorry, what are you doing?' And you're like, 'Oh, I'm doing it the right way,' and people are like, 'No, not at all. This will never work.' And you're like, 'Oh, you know, let's not let's not argue about that, because I'm fairly sure it will work.' And then, in their most well meaning way, people will be like, 'Okay, here, this is how you do it.' And you now have two routes that lead to the same kind of goal. And then you realize, okay, good, there isn't one truth. As nice as this would be, you always make some compromise or something works because of you know, climate or access to local chemistry or other things, or just to custom. Yeah, it's really amazing. The last few years, I've been kind of trying to soak up as much knowledge from this Swiss printmaker, Ernst Hanke. And he's been in some of the last videos, and I've never gotten this many comments on the way he etches stones because it's the hottest etches I've ever seen put onto stones, but he knows what he's doing. He's done this since he's 15, and he's 73 now. So he really knows what he's doing. And if you show this to people, they're like, 'Okay, good. So you burned your entire washing. How are you going to redraw your stone?' And you're like, 'No, actually, this works.' But you know, this works because the person knows what they're doing. And that's so cool to see. And it's so humbling at any given time to realize that, you know, there's so much more to pick up and to hone and kind of fine tune.

Miranda Metcalf It is funny how non-standardized the printmaking practice is. It seems like something that's been going on, you know, in the case of etching, for 500 years, that all the kinks or all the little nuances would have been worked out, but there's always something more to learn. There's always some weird little trick hidden away in a corner of Thailand that you haven't heard of yet. And I think it's part of what makes the practice and being connected to the larger culture of it so rewarding.

Patrick Wagner Exactly. And also that, you know, there's these big, big differences in possibilities based on how your shops are set up, but they're just differences, not limitations. Like I have these nice videos playing in my head at the same time, and one is, you can find it on YouTube I think, it's from Highpoint. It's, oh, I've forgotten his name, Cole Rogers, I think, the master printer there, he's coating a screen in some of the videos, he's just coating it super nice in this one swift motion. And then I think he turns to the camera and says, 'This is how it's done. This is how you code a screen,' or something, which is, you know, this is how you code a screen in one swift, nice motion. And there's this other video of this guy sitting on the floor in a shop in India, and he just pours emulsioni onto the screen, and he has, I think it's a credit card. And he just sort of uses this little plastic card to coat the entire screen, to move the emulsion around and coat it and then smooth it out from the backside in what is obviously a very trained and skilled motion. And you were like, yeah, of course, if they had the setup that you can have elsewhere you'd do it different, but both people are screen printing at the end of the day. And one is a pro shop, and the other is, I don't know what they're printing, for local merchants or something. But it works. It's amazing. And, you know, that goes from... after studying in Bucharest, I went to Bergen. And it's been night and day, of course. Bucharest was like, me and the other students, we'd cook up our own hard ground in the basement. So we would just take naptha, tar, turps, beeswax, and some other stuff and kind of just have this hot plate and boil it in this bucket and just lift our T shirts over our noses and be like, you know, it's safe, I suppose. And then you go to... and, you know, we'd make great prints there. But it was literally impossible to get anything else but steel to work on. So we all had to have belt sanders and get the steel as smooth as possible, because there was no access. And then after that, the next half year was Bergen. And that was where Jan Pettersson had been teaching, I think he's now teaching in Oslo. And he wrote these great books about photogravure. And he had set up the shop, the art academy there. And he was just setting up Trykkeriet, which is a center for contemporary printmaking in Bergen. So you have two spaces in this town that are perfect for making photogravures, copperplate photogravures, which is, they have these nice climate control setups. It's kind of these airbrush thingies in the room that keep the moisture at exactly 80%, if that's what you want, and you have this plate whirler for your gelatin paper, and it dries the right way, and you have a plate spinning. And it's amazing, of course, and you can do these works elsewhere, but it's so much harder to fight conditions. So when I was later studying in Helsinki, and I wanted to make photogravures, it was actually the smartest way, I felt, was to go back to Norway and book shop time there and make the works there. Because I'd be like, okay, I can waste two months of my time trying to set up a perfect environment for photogravure in Helsinki, or I can just go somewhere else where it's conductive for that type of work. And I think that's kind of something that's always good to keep in mind is that people in Romania, we're etching the same, you know, same passion that you do elsewhere and get great results. So, the good shop didn't automatically mean great works, nor did the adverse conditions mean that the work was shitty.

Miranda Metcalf And I think sometimes it can even be the other way round. Because if people are fighting through difficulties, they have such a fire in their belly to create these images. They can do really incredible things, where if everything is just easy, there's a kind of casualness about your practice that you can fall into, I think.

Patrick Wagner Yeah, exactly. I think that's why I got so into these works of Nigerian printmaker Bruce Onobrakpeya, because I think he learned printing somewhere in London, or in England, at least. It's kind of vague on his biography and I'm not fully up to date, so I'm sorry, maybe that's not 100% true, but I think he learned somewhere in Europe and he went back to Nigeria and got the wrong assets and got all sorts of other problems. Because, you know, it wasn't as easily available as it was where he learned, but that led to some really amazing discoveries, where they were using epoxy to fix holes in a plate. They had etched plate too strong and it had gotten a hole. And I think he took it to a car body shop where a friend of his was working, and they were like, 'Oh, that's cool, we can patch it up with epoxy,' which they did. So the hole was fixed, but then the epoxy doesn't etch. So you had to carve it. And where the drops of epoxy are on the plate, they're now relief. And so he creates these works that are called "deep etchings." And they're amazing. I think he works in sort of several layers of topography in that plate, like, he wipes parts of it intaglio and he rolls up others because they're higher, and they make these amazing works. And so that only was created because of conditions that existed in his shop at the time. And the availability. So always trying to keep that in mind when making works. And people are like, 'Oh, what should we buy?' And you're like, 'Just take what you have, it's good, and we'll make it work somehow.'

Miranda Metcalf So speaking of the Nigerian printmakers, you were doing printmaking interviews long before Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend) came along. So I'd love to hear you talk about that a little bit and how that process was for you and who you got to talk to during that time.

Patrick Wagner Yeah, you know, but it was completely different than Pine Copper Lime. So like, I was way less professional, and way more based out of just curiosity. Like I said, you know, you spend too much time online and looking up things and then you were like, 'Okay, good. There's only that much material. I need more. There's two books on this guy.' And in Bruce Onobrakpeya's case, I think it's safe to say he's in his 80s now. So a lot of the material that exists on him probably exists pre-digital, in some way. And every once in a while, you kind of forget that, oh, yeah, stuff exists offline, too. You just can't access it from the convenience of your home. And that's true for German collaborative shops that for some reason work very different than Americans. And that's true for a lot of other people that have either not been fortunate enough to have content created or have worked before content creation time, in digital content creation time. So I was like, 'Okay, I need to reach out to people, but also, I need to give it some sense, it has to have some format, that kind of benefits others.' Because I am spending a lot of time preparing for interviews or something and then doing them and sort of... and also knowing how much of a sloth I am, it's kind of good to know that you have something, some kind of goal to work towards to. Because otherwise it can just be a phone call, and I know it and then I still have to generate value out of this, or at least it feels like I should, because I've made all this prep work for it. And so I did text-based interviews, that were on the Tumblr. I tried to do this in a larger format for my MA project, and it kind of, I kind of had to shortcut it at certain times, because at some point realized that I was in over my head. But long story short, I contacted a couple of people, and Bruce, being kind of maybe the person that was most important to me, because I had only been given a book about him with black and white images and a short story about his life that was published in Nigeria. So there's no way to contact the publishers because there's no phone numbers or something. And through a lot of persistence and calling the wrong people, I eventually got his phone number, which was already quite this adventure, because you have to convince completely random people in Nigeria that you are legit and you're worth their time. And eventually we talked and I had bad recording equipment because I was so focused on other things. So I just had to put my phone on speaker and have the laptop recording, running next to it. And it's very sub optimal. But it worked. And I got to ask my questions and got to learn a lot of stuff. And I did that with Mark Herschede, that's actually not an interview, but I just called him because I had so many questions about his shop. He runs Haven Press in Brooklyn. And I think I saw works that he published online. There's a Norwegian mezzotint artist called Tom Kosmo who makes amazing works, who I've been aware of because I've been in Norway for a while but we never got to talk or something. So then it was quite nice to have this sort of badge, self-applied badge, where you're like, 'Oh, I make interviews. So hey!' I can just reach out to you and people are like, 'Oh yeah, you make interviews. That's totally cool, that's legit!' and then you could talk to people.

Miranda Metcalf I would love to chat a little bit deeper about Black Heart Press and, is it a collaborative studio, is it just sort of the name for your own practice? Sort of define, like, what it is, and when you started it.

Patrick Wagner Black Heart Press is... it's not a collaborative studio. It's the name for my printmaking online presence. Black Heart Press originally was a blog, it then moved to Tumblr in 2011. And it's sort of now kind of more or less transitioned onto Instagram. It's an umbrella for all these things. It's an umbrella for the visits to all these print shops that I've done, because I've been quite fortunate in terms of travel grants or travel possibilities in the last years. And having this network, it seemed only natural to sort of visit all these shops. And it also is where I post my own works and where I post about the shop that I'm setting up now. It helps to be name consistent, at least, so that you can be like, 'Okay, I don't know how the guy is called, but it's Black Heart Press on Instagram, or Black Heart Press on Tumblr, or something.'

Miranda Metcalf And it's very memorable, too. Names like that always stick in people's minds better than than human names, right?

Patrick Wagner Yes, exactly. I know most people by their Instagram names, and I'm like, 'Yeah, what was their real name again?' Yeah. And I mean, Black Heart Press is a total ripoff of the band Black Heart Procession.

Miranda Metcalf Oh, yeah. So Black Heart Press, you said it's sort of your own work? Do you want to talk about that a little bit, and what your own practice is personally, and sort of what it looks like and where it comes from?

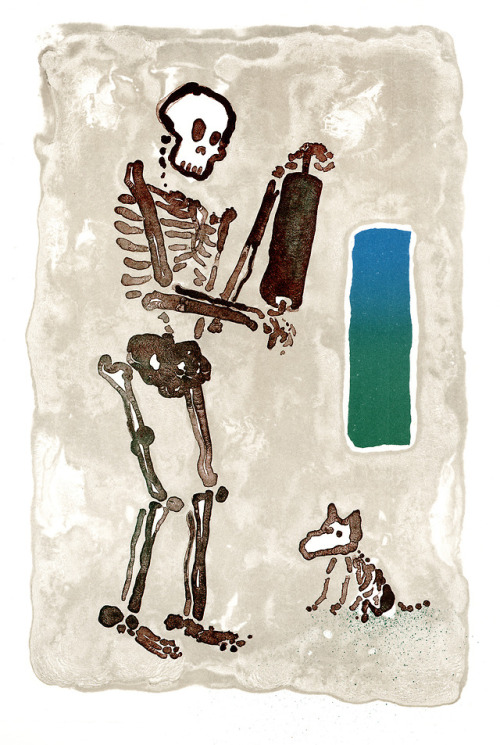

Patrick Wagner Yeah, I don't know. Currently, I'm sort of reconnecting to that a bit. Because I've been a fine art educator for the last five years. Which means that - I'm not sure what the American equivalent is, I'm a junior lecturer, it's like kind of the lower - or I was a junior lecturer, because I've been let go and the shop's been closed. But that's what I mainly did. And if you do that on basically any percentage level above 50, there's no time for your own art practice, at least I didn't have the energy. I always admire everyone who's teaching and who gets to get anything done. Because when I come home, I'm like, too tired to play video games. Because I just need to, you know, rinse all the student questions out of my head and think about something, and then with whatever financial situations that you have as low-tier academia, you can't even afford a studio. So you can work in the school studio, but that means that whenever someone finds you there, you're working. Like, good luck, it's Sunday night, and you wanted to do some quick editioning, but there's also two people in the shop and they ask you, which makes sense, because you're the person that should be asked, maybe not on Sunday night, but it's so hard to get good work done. So I make etchings and I make lithographs, and since two or three years, I've really gotten into this kind of Schnellpresse printing in this, you know, Ernst Hanke style. He's got his own great method of working, and I'm trying to emulate and copy as much skill as possible. I wish I had started earlier with that, but that's what I'm doing. And I draw skeletons. That's the only thing I can draw, sort of. And rainclouds. If you like medieval prints, then you've come across memento mori, totentanz, dance macabre, dance of death, image traditions. And those, I feel, in these turbulent times right now, are as valid with all the environmental catastrophes looming as they were in the 1500s. So to me, it seems valid, I will probably not get invited to a biennial or something due to relevance, but that's fine, because they give me joy.

Miranda Metcalf No, I love that, that makes a lot of sense. I actually have my master's degree in 16th century Northern European printmaking. When you're talking about any of that kind of like, dance of death, and obviously it's a little bit later than some of the... plague and that kind of thing, but I always loved that work. And I wrote a paper about - I'm embarrassed to say his name in front of someone who's a native German speaker, but the very Americanized way of saying it is Hans Baldung Grien. So you know, in his witches and everything like that, I loved studying that. And I can definitely, now that you say that, I can really see that in your work. Because your skeletons certainly have a life to them, like the ghoulies from that time, and as you say, all the uncertainties and catastrophes that we know of that seem to be on the horizon, let alone those that we don't, it does seem a very appropriate time.

Patrick Wagner Yeah, it's sad but true. So yeah, but I feel like I don't have an artist practice in the way that I live off my art or something, or strive to live off, because that seems impossible somehow. And I love collaborative printing, so I think that that's always going to be a part of my practice as well, is to work with others. Ideally, I'd like to continue teaching, because that's super fun. But I'm also setting up my own shop in the middle of nowhere in Sweden. So eventually, I'm gonna have some some place to invite people to.

Miranda Metcalf And actually, if we can double back for a second, when you were talking about your own work, you were saying you were inspired by... I think it was, was it a German word?

Patrick Wagner I probably said totentanz, it's just the German word for a dance of death. But you know, it has this strong image tradition. I guess there's a foreign - there's usually how many other... depending on who did it, there's so many artists that did the totentanz at some point in their career. There's Notke, there's the famous Lubeck totentanz, the dance macabre or dance of death from Lubeck. And it's usually skeletons dancing, or not dancing, but it's skeletons and people, people of certain crafts, and you know, the higher point being that death comes to everyone. So with Holbein, there's a really lovely series where there's one where it's called "Death and the Infant" where, you know, the skeleton leads the child out of the home, or something. There's the king, there's the rich person, there's everybody, and kind of it shows that this is the one unifying quality that we all have is that we're mortal. No matter how big the company is you're running, and no matter how much other things, or how poor you are, and I guess that was, in a way, disconnected with a lot of people, I suppose. And I think they were meant to pacify, to say to people, it's okay that there's so many injustices, because eventually - like, I think this must have been something from the rich people that commissioned these works, also - to be like, 'Okay. Eventually, just remember, it's fine that I have more than you.' From the church. And I think that connected really well. And then since it's skeletons, and you can't tell, especially not the anatomically incorrect way I draw them, you can't tell sex or race from a skeleton, which is also wonderful, because that's, again, the unifying quality we all have. So yeah, but I think the word was just totentanz.

Miranda Metcalf And so, do you think that the longevity of an image like that, and the fact that you're still drawn to it, I'm still drawn to it, do you think it comes from the same places that it did in its inception? That it is this unifier, that it does have a kind of dark comfort in that? Or do you think that it's evolved in some ways?

Patrick Wagner Yeah, I think that there is a unifier. I'm not sure if it if it has evolved, I think it's kind of the most basic thing, sort of in a way. And of course, it's more fun when you're young and kind of cocky, and none of your friends have passed or something. And you know, nobody that's close to you has fallen ill or passed, and you can just be carefree about it. But as you move on, I think we all have stories in our lives that touch mortality in one way or another, and usually in a way that's really close. Then you realize, like, okay, it is actually a strange sort of thing. These days, it's so removed, I think, from our considerations in a lot of ways, because science is amazing. And you can resuscitate people and so many things that were, you know, when you look at artists, you read their biography, and they're young and promising, and then they get the flu and die. Like Schiele or something, and then you're like, oh, damn. But soon, antibiotics will no longer work. And we might get there again. And so I think that's why it works with so many people, and maybe you have the humor that you enjoy it and you can see kind of a sense in it. Or maybe it's too close. I've gotten both reactions. For the Kickstarter to move the press, I was at Ernst's place in Switzerland, and we printed and so out of a whim, I decided that one of the prints was going to be a portrait of him, which is a skeleton because I can't draw. I could, but it would just be like a cartoonish kind of thing where you recognize him because of the hair or something. So I drew a skeleton and the skeleton holds a litho roller, and I drew his dog as well. And the dog's name is Happy, and it's white dog. So I drew this little skeleton dog sitting at the feet of that skeleton. And there's the bar of color and it's Ernst's favorite colors. It's like a blue fading into a green that's, in German, it's "nilgrun," nile green. Not sure if English speaking people know what that means, nilgrun, it's a really nice color. And you kind of need it if you want to mix a nice turquoise without using white, then you need that kind of green, if you just want the white from the paper and transparency. Anyway, so we made this print, and we were printing all the colors from the same stone. So the image comes up fairly fast, like you're shaping it fairly quick. But you're also, as I draw the background, that's the first time we see the background, or the background plate or stone doesn't exist until it's time to sort of resensitize the stone and draw that part. And so as it comes up, and we're looking at the proofs, and we're deciding - "we" is Ernst and his wife Erica and me, the three people in the shop - and we look at the print and say, 'Okay, should we commit the entire stack of the edition to this background?' And I said, 'Yeah,' and Erica, she's like, 'Oh, my God, this is perfect. We're gonna use this for the death announcement in the newspaper.' And I'm like, 'Whoa, I didn't mean it like that,' you know, I was just like, it was just the humorous little touch, you know, to what has essentially become a really good friend of mine. So for a moment, it was funny that I was the one taken aback. And Ernst loved it, his wife loved it, and I'm not sure what the dog thought, but, you know, everybody was kind of positive about the image, and it wasn't macabre or something at all, it fit really well. Because they had the right sense of humor to sort of see that and enjoy that image. And I've had other people that were like, 'Okay, this is too much. Too many skeletons, and it's too close for some comfort.' And that's fine as well. And I think that's something I always try to be respectful of. But that's why the humor has to be in there in one way or another.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, a couple of things kind of come to mind when you're telling that story. And one is that I think, sometimes, it's easier to joke about your own death than to hear someone else joking about theirs. But also, I think, in terms of that kind of sensitivity, I think it can also come in waves, you know, if something happens where I've experienced a death close to me, there's always a time period where I can't, you know, I notice it in a more sensitive way. And then six months on, I'm ready to listen to a murder podcast and make jokes again. It is interesting how we, at least for me, it's cyclical, between the reality and the way that our brain kind of separates it or gets its coping mechanisms back, I guess.

Patrick Wagner Yeah, absolutely. And then, you know, there's also so many dimensions to it. I have this friend, Katie Mack. She's amazing. She's an astrophysicist. And her favorite topic is, I think, the end of the universe as we know it. And it's amazing, because it's going to be spectacular. We won't be around when it happens, or we don't even know, I guess. I shouldn't be talking about it, because I have no idea. I just sort of know what she talks about in her lectures and in her poetry and her words that she puts out, but it's amazing. And it's all encompassing, and it's fascinating. It's absolutely fascinating, and will also most likely, you know, be the end of all things because that's what the end of the universe is. But there's something sort of comforting about it, that there is an end of sorts, and I suppose in my work, this kind of comes back, also, to... I mentioned this fire in 2016, that fire ate my entire archive of all the works that I'd made until then, from, say, 2006 when I started to 2016 when that house had the roof burned down and the water kind of messed up the entire place, and we couldn't get in because it was... whatever, long story. Anyway, all the works are gone. And you're like, 'Oh, okay, good. So what do I do?' I've recently applied for a job in Germany. I didn't get it, but I was invited to the interview and they wanted to have physical work samples, which is old fashioned. I was like, 'Okay, whatever.' And so I brought this A4 folder, like letter size folder, with three random prints that I had lying in my apartment. Complete randomness that they were there and didn't get destroyed together with my studio that was located at my office, because that's where I was all the time anyway. And I was like, 'Okay, these are all the works that have. Full disclaimer, there's a lot more, and I can show them online and show them whatever, but if you want to see physical works, these are some new works that are printed, and this here is like my archive.' And there's no there's no archive of student works anymore. There's no archive of works that I've made of projects that I'm really proud of. Because they're gone. And that's cool. I'm fine with it now. I've been in shock, and now I'm good. But it's still kind of, at certain times it comes back and you're like, 'Oh, yeah. You'd like to see those prints? Yeah, no, they're gone.' Or, you know, I'm not going to make any money with them ever, even if there's no interest in whatever works I made, because they're gone. So I guess that kind of also helps with the entire, the whole subject, kind of the fascination with it, in some way. I don't know, I guess you have to relate to it.

Miranda Metcalf I get it, in the sense that a couple of... it was actually the week, or maybe even the day, that I launched the Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend) website, I accidentally deleted all of my files besides my Pine Copper Lime files. The Pine Copper Lime files, I just had happened to put in a different section of the computer, and I had just deleted everything. Everything I'd written in graduate school, all of my photos, photos of my beloved dead dog, who was my world, like, it was all gone. And it was jarring, but also weirdly comforting. You know, because there was a... kind of a cleanness about it, a weird sense of bittersweet freedom, and sort of like, 'Oh, I don't have to worry about carrying that around anymore.'

Patrick Wagner Like, I think the sense of loss will later be the same, because I mean, who has physical photos these days? And so I think if you kind of lose some hard disks now or, you know, whatever, I think this is as dramatic as burning up your old photo albums or something. Probably even more widespread, right? It's all you have. And you're like, oh, it was just digital information. There's no box in the attic with old negatives or something. It's just gone. So that's how it goes. There's no point in dwelling too much, I suppose, on that.

Miranda Metcalf There's a kind of freedom in not being given a decision, if that makes sense.

Patrick Wagner Well, I'd like to have my stuff back, you know, just for the record, but there's some things that you just can't change. And you just got to live with it. I guess that's, once you've managed to accept that... I think there's this wonderful scene in The Simpsons where Homer is mortally ill or something and he goes through the five, or seven, whatever, stages of acceptance within... like, he gets this leaflet, and he goes through those states within like 10 seconds. And it goes like "your progress is remarkable" or something. And you're like, 'Alright, good. That's done.'

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, he's eating the puffer fish, I think is what's happening. It's such a brilliant early Simpsons episode.

Patrick Wagner Yeah, I never missed an opportunity for a pop cultural reference.

Miranda Metcalf So I would, though, because we've talked about it and because I'm curious, maybe kind of wrap up by talking about your sauna project, which is the other side of things.

Patrick Wagner Right. So it's not my project. I'm just kind of its most devoted disciple. Art Sauna is a communal sauna experience. It was created in 2014. It's a sauna on a trailer. A sauna is a Finnish thing. It's a room that you heat up to about as hot as you like it, or can get it, and then you throw water onto the stones and it creates a steam, and the Finnish word for that is "loyly," and that steam is amazing. And you just stay inside for as long as you want to or can stand it or feel that it's fun. And then you can go out, and preferably, you go out to a really cold place because by the time you leave the sauna, you're really hot. And the best place for that is a hole in the ice. In Finnish, that's called "avanto," in Swedish, it's "isvak." And that's the Art Sauna in short. The Art Sauna is the brainchild of Anton Wiraeus. Anton was a printmaking project student at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm in the first year when I started working there, and I had lived in Finland for the last four years, approximately, where I was working as an intaglio printer in the shop of Tuula Lehtinen, printing lots of cool stuff with her, for her. And the only way you can have friends in Finland is if you drink, which I don't, or you have sauna, which I love. So, yeah, I was good there. I moved to Stockholm because I got the job. And Anton, being Finnish, or half Finnish, we made some prints that were actually posters for the sauna sort of, or like, drawings of the sauna. And so we talked about it, and he was like, 'Oh, you miss Finnish sauna?' And I was like, 'Yes, I do.' He was like, 'You should come to the Art Sauna, because it's a trailer and we just drive it out to...' like, every city has these sort of off spaces, like not abandoned spaces, but kind of... here, in Stockholm, it's Liljeholmsstranden, it's close to a concrete factory. It has an old ink color factory next to it that's like, decommissioned and sort of, you know, it's full of graffiti and kind of kids that get a thrill out of skating the fence and you know, skating around the ruins or something. And it also has these piers, Stockholm has a lot of like public bathing places. But these piers are in a really unwelcoming area. There's old train tracks that were, I suppose, supply trains for the concrete factory, pass there every once in a while. And that's where Anton or I, mostly Anton though, drives the sauna. And then you just park it and heat it up and you chop the wood, and everyone's welcome. And that's kind of mostly the Finnish spirit. Usually, people are decently dressed and all this. But there's also some hardcore people that feel that clothing don't belong in the sauna. And that's most likely going to happen at some point, too. I had friends visiting from New York, and I was kind of like, 'Okay, I'm not sure how down you are with, you know, our loose European ways. But you know, there might be a naked person in that sauna, we'll just see. But most likely, they will be dressed.' And we come there and the door opens and Anty steps out and he's a Finnish carpenter, and he's buck naked, and I'm like, 'Hi Anty!' And he's like, super casual, because he's in the sauna all the time. He's like, 'Hey, how are you?' And just side glances at my friends, and they're like - it's actually, it's PJ and an Audrey, PJ the riso printer. I think he's at Robert Blackburn's. But anyway, he's there, and he was looking at me like, 'Okay...' and I'm like, yeah, welcome. And Anton just goes and does this backflip into the water. And we're having a great time. They're having sauna, and we're all enjoying it, and Audrey ends up making a painting about it. And that spirit is kind of what the Art Sauna is all about. It's a lot of friends that I've made in the sauna, which is really helpful for me, because that meant I got to meet people that were not printmakers, or my students, or colleagues, because that's literally everyone I met because I moved to Sweden because of a job. So you know, we know how that is, you only hang out with those kinds of people. And it's a huge lesson for me, because I'm not necessarily... maybe in 2014, I wouldn't have been that welcoming as I am now. But it's, if someone else teaches you what it means to really sort of open the door, and that could be the door to your sauna or the door to your shop, and be like, 'Yeah, you're welcome, you can come in,' you can have the funniest people showing up. And at times, you know, it's way easier, just like, keep it private and keep it locked. And no surprises and it's nice. But once you've dared to kind of be inviting, it's really fun. There's random French tourists, they're like, 'What are you doing here?' We're like, 'We're having sauna, you can join.' And they're like, 'Really?' And you're like, 'Yeah, just hop on in.' And suddenly you have a French couple in their underwear sitting in the sauna and having a great time. And it's December. And then they go swim and it's amazing. And it costs energy, because it is, you're sacrificing a certain form of private space, but you're sharing. And I think that's why Anton's project is so amazing. And that's why I am there so much volunteering and whatever. Chopping holes, I love chopping holes in ice or chopping wood, so lots of chopping. Yeah, that's the sauna.

Miranda Metcalf That sounds like such a great project.

Patrick Wagner Yeah, it's great. I think he should like... I don't know what the deal with Stockholm is, but I feel that every year he should get like one award or something, because there's certain initiatives to kind of... you know, we talk so much about how printmaking is democrative because you can lower the price and reach more people. And the same way the sauna project is sort of, you know, for the people. Because you can pay volunteers what you want if you want to, you know, pay for the wood, because it's not free, and someone had to build that thing and it's on a trailer. So it has to, you know, someone needs to drive it out with a car, and it's work, but it's also free, and there's demand for it in a certain way. The city needs kind of social spaces. And it's a spot in the city that is sort of, like I said, overlooked. It's not shady, but it's also it's not, oh, how lovely, by the beach. But it's a way to reclaim that certain space. And it's a way to sort of say, okay, you could make this into more parking lots or into random, overpriced apartments for the people that can pay for such expensive apartments in the center of town, or you could make it into like a social place that would benefit everyone living there. And one opportunity is with the sauna. Where it parks, there's no parking lot, it stands on the tracks. And so every once in a while, depending on where it stands, there's different securities that are responsible for this area. And usually the project itself is so charming and so honest, in itself, that we've never gotten a ticket yet. But there's people that are like, 'You can't stand here,' and you're like, 'Yeah, but we're having sauna, so why don't you join us?' And they're like, 'We can't because you know, I have to tell you guys that you can't park here,' but then you're like, 'Okay, what do we do? Because now there's like, seven people in underwear, dripping wet, standing in front of you, we can move the sauna, but where do we move it to?' And they're like, 'Oh, I don't want to ruin your day, but if you drive 20 meters further, come this sign, my jurisdiction ends, and it's someone else's problem. If you stand there, it's fine. Because then I don't get trouble with my boss.' And we're like, 'Alright, you know, we can do that. Sure.' We move 20 meters further, other end of the sign. But so far, there's never been a problem with it. And I think that comes from the niceness of the whole thing. I mean, Satoru, the guy from Japan, he had sauna with us there. He was like, 'Alright, now we jump in?' I was like, 'Yes, yeah, we jump into the water.' And yeah, it was lovely.

Miranda Metcalf And the Japanese, of course, have their whole very old, communal, warm bath tradition. So I'm sure it felt right at home.

Patrick Wagner Yeah. And you get to have tattoos, so that's cool. Which you don't get to have in Japan.

Miranda Metcalf So can you let people know the best way to find you and follow you and offer you teaching positions?

Patrick Wagner Yeah, the best way is @blackheartpress on Instagram. It's blackheartpress@gmail.com if you want to send me an email. I think that's the easiest way. Simple as that.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, simple is good, as I said, you can remember it. So yeah. It's been an absolute pleasure chatting with you about everything. And yeah, I hope we can stay in touch and have you back on sometime to dive deeper. I'd love to talk more about African printmaking and international exchange and your time in China and the polargraph, I had all kinds of notes we didn't get to. So I hope we can do it again.

Patrick Wagner Sure. Absolutely. I'd love to.

Miranda Metcalf All right. Sounds good. Thanks again, Patrick. Have a good night.

Patrick Wagner Thank you. The same.

Miranda Metcalf Well, that's our show for this week. Join me again in two weeks' time when I chat with Craig from the Awagami Paper Factory. And let me tell you, I was blown away by the incredibly ambitious projects they're up to there and the eight generations of history at the factory. Craig talks about their collaborations with artists, calls for art, opportunities for residencies, maybe dropped that they're looking to hire a master printer in the future (cough, cough). We also get into the differences between Western paper and Washi - don't call it rice - plus Awagami has generously donated 50 sheets of editioning paper for a giveaway that will take place as soon as the episode drops over on the Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend) Instagram. So check out the link in the show notes and join me there. This episode, like all episodes, is written and produced by me, Miranda Metcalf, with editing help from Timothy Pauszek and music by Joshua Webber. I'll see you in two weeks.