episode two | nathan meltz

published 21 nov 2018

episode two | nathan meltz

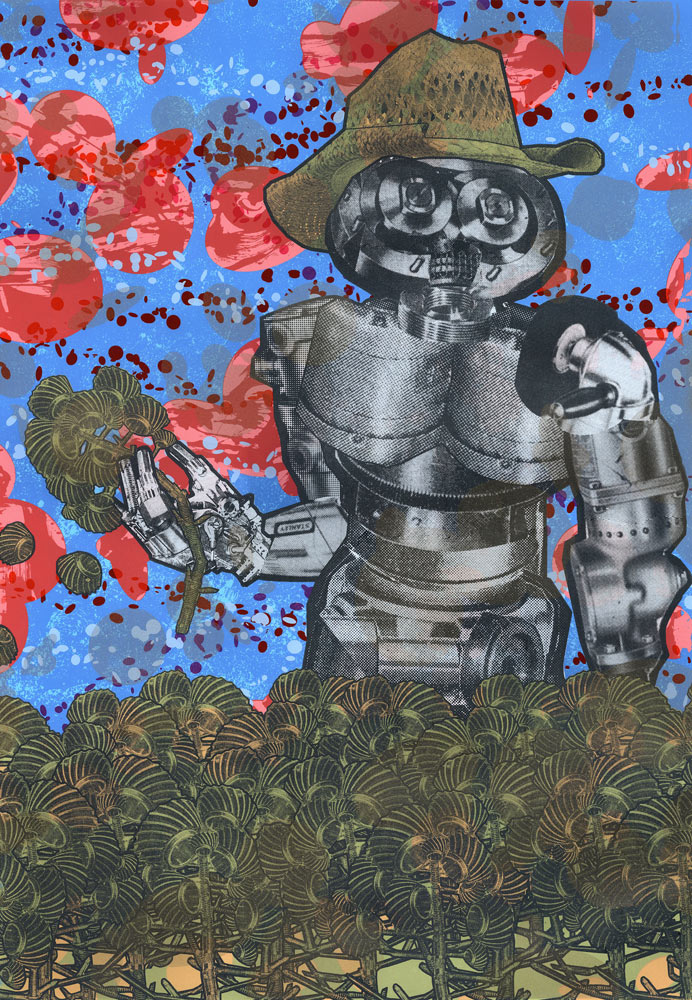

In this episode Miranda speaks with Nathan Meltz about his founding of the Screenprint Biennial, his time in the music industry, early anarchist publications, and robot porn.

Miranda Metcalf Hi, everyone, and thank you for tuning in to the second episode of Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend), the internet's number one contemporary printmaking podcast. As you'll hear, even though this is the second episode I posted, it was actually the first interview I ever did. Nathan was kind enough to be a guinea pig for me in that way. So you'll hear that I made the mistake of suggesting we do the interview via Skype, but not suggesting that we do it without the video. About halfway through, it finally occurs to me that we'll get better sound quality, if we just have the audio. So you'll hear that change and just chalk it up to a young podcaster cutting her teeth. But you're in for a real treat with this interview. Nathan is super smart, super articulate, and has wonderful views about the past, present, and future of printmaking, about community building, and about robot pornography. Here's Nathan.

Nathan Meltz Hello, Miranda. Greetings.

Miranda Metcalf Thank you for being my first interviewee on the podcast.

Nathan Meltz Happy to be here and talk a little bit about print work.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, I'm excited. Um, can I ask you to tell us a little bit about yourself? Who you are, to get started, and then we can dive into talking about you and your work and everything else.

Nathan Meltz Sure, so I kind of wear three hats. One of them is a teaching hat, in which I'm a lecturer in the department of the arts at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. And the other hat is my art making hat, in which I make art that talks about controversies in science and technology and how technology affects everything from family and food to politics and war. And that practice involves a basis in collage and printmaking, but extends into animation, sculpture, and installation. And then my third hat, my curatorial hat, in which I founded and every two years coordinate and curate a Screenprint Biennial.

Miranda Metcalf So if you can, I'd love you to tell me the story of how you came to printmaking and how it ended up being sort of an intrinsic part of your practice, but obviously, we've heard, not the only part of your practice. And sort of how that happened, and how you see it fitting into your entire work.

Nathan Meltz I think I am like, part of a generation of print people who really took the gig poster as the gateway drug for print work. I'd done a little bit of it as an undergrad at the University of Wisconsin. But then right after I got my undergrad degree, I made the best choice of my life slash worst choice of my life of spending the next year just touring in a band, and then needing merch to sell. And because like nobody makes money playing really, but what you make money off of is all this stuff you can sell. So printing shirts and making posters, a lot of times you'd sell the posters as sort of like, show artifacts. And that got me back into screen printing, and something that I started exploring more and more. And then eventually, man, I was kind of a late bloomer in terms of art. I honestly, throughout my whole 20s, took music much more seriously than visual art and performance. And it wasn't until, you know, I turned late 20s or 30, and I actually started making prints that I was like, oh, I kind of like some of these. And, you know, kept working on them for like, you know, like, the 10 years until I was finally like, oh, okay, so I'm now like, I like these and some of them are - don't totally suck! And then as part of that, going into grad school, couple grad schools, and getting into the world of print and really enjoying the community of print. And even though you know, primarily I just do screenprint, you know, I've dabbled in relief and letterpress and a little monotype, I'm not anywhere near like some sort of master printer, but part of me - and sometimes I will do projects that are just print products. So like the most recent project I've been doing, my Strangling the Fascist Viper, has been all large, fairly large format screenprints. But that's kind of the exception, where usually I'll do some sort of sculpture and animation as well.

Miranda Metcalf I think one of the things you said about the community around printmaking is why I think a lot of people kind of, they, they may come for the aesthetic and stay for the community sometimes.

Nathan Meltz Man, I don't know how many people I talked to other medias, like painters, and they're like, oh man, I'm so jealous. You printmakers, like, have all the parties, you have SGC, they just would kill for it. You know, maybe ceramicists have something somewhat similar. And like, there are photography conferences, but then they have the whole bifurcation between commercial photography and fine art photography. We're really lucky. And we have something that's definitely a catalyst for lots of ideas.

Miranda Metcalf Do you think that's because it has this studio as a communal space? So it sort of draws personalities who do like to interact as they work?

Nathan Meltz That's a really good question. You know, obviously, part of the answer is yes. But then a part of me is thinking about, oh, I think I've known printmakers who are total misanthropes as well and like did have their own little press and work independently. But I think it's it's working with each other. And then the fact that there's a community of like the master printers, people who just really like printing other people's work. And I went through a period where maybe every year I'd print one edition for someone else, just because it was somebody's art I was really amped up about. And even though, like, it's more stressful, printing other people's work, it was something I was excited about. So yeah, it's kind of - there's that communal, and... it doesn't help to work in private, I don't think, in this discipline.

Miranda Metcalf That's interesting. Do you think that that's specific to printmaking that it doesn't help to work in private or just maybe generally for art practice?

Nathan Meltz I'm sure there's some people who like pulling up and being individual, but I'm sure with a ceramicist, it helps to have a shop of people. I think if we, as we get away from the traditional concept of like, "the lone genius" making art by themselves, and realizing, like, projects take groups of people. You know, I'm in this performance music project now, and it's like four other people. Most good things come from collaborative help and people working together. So printmaking kind of, like, was perhaps into the 21st century quicker than other media, where they saw the writing on the wall, but they've always just worked as this collaborative media and other media artists may be catching up.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, I think that, as I see text and sort of, theories about art, that really are interested in destabilizing that idea of the "lone genius," as you say, or even the sense of, of authorship as something that can come from a vacuum, printmaking seems to kind of, as you say, fill this space of, well, we've been there all along, we've known that.

Nathan Meltz It's like, did the death of the author start with Albrecht Durer?

Miranda Metcalf Yeah. Which is interesting, because as I'm just thinking about it as a print nerd historian, you know, Durer was one of the first people in the world to sort of take a copyright case, because his work was so popular that people were imitating his signature, you know, that famous sort of "A.D." So they would make work in his style. And then they would also basically sign it as him to try and sell the work because he was well known and, and there was a market for his prints. He took a case to a high court in Venice, I believe, and he lost. So he was at a time when that idea of authorship, at least maybe in the context of printmaker, wasn't quite there yet.

Nathan Meltz So there were, like, Italian printmakers who were ripping him off? Is that why went to Venice?

Miranda Metcalf I think so. This is drawing back to, you know, one thing in graduate school, I'll have to maybe look it up again. But in the 16th century, as, you know, I think as still contemporary art history reflects that, it seems that there was the belief that the northern work was somehow lesser, less refined, than was going on in what is now Italy. And so there was this, generally speaking, people in the north trying to imitate people in the south. But it was a little bit different with Durer, because he was so well known and so beloved in his own time, you would get people in the south trying to sort of be like him, get that sense of the bodies that he could do that were so great. So, yeah. So I also wanted to, you know, talk a little bit more about what you said was your your curatorial hat, just sort of the Screenprint Biennial, you know, I'd love to hear the story of how that came to be as well.

Nathan Meltz Sure, sure. So do you know Richard Noyce, he's like this English art historian. And so Richard Noyce was giving this talk at the Impact that was in Dundee, Scotland, and I forget what year that was, like 2013, maybe. Anyway, he's giving some talk, I'm attending it, he's a really good speaker. He's really passionate, really into print, and political prints. And he mentioned this sort of off handed, off the cuff... I'm just gonna make this up. It was like, some experimental aquatint biennial in, you know, some East European country, you know, Latvia, back in 1973. So something pretty obscure. And he talked about it as a biennial. And I was like, 'Oh, boy, that's interesting.' So, to that point, I thought, Wow. Well, is there a screenprint biennial? There must be. So I started looking it up right away and couldn't find anything. I found like in Japan, they have Meshtech Screenprint Biennial, which, Meshtech apparently is some company that makes screenprint materials and it's just in Japan. It's kind of weird. So everything's really small. And there was no, there's no North American, South American - there's no Western Hemisphere screenprint biennial. I decided, well, there should be. And so I decided to start one. And then really just kind of went for it. It was kind of past the grant cycles for that year. So well, first of all, I had to find a venue. And like, I'm in Upstate New York, so I just found... there's an art center here in the capital region that has, like, a nice gallery space, I approached them. And they're fine giving me the gallery for this fall season. And then, but again, no money whatsoever. And it was too late to get grants. So I did a super foolish thing and I decided to start a Kickstarter to raise money for a catalog and to pay for things, and it was successful, but it's a total fucking drag. It's a terrible idea. But it was successful, gave enough money to pay for a catalog and pay to get some help - no, I didn't pay for an installer. It was purely just for a catalog. That first biennial was an invitational. And it was inviting, half the people, I kind of knew, and the other half, people I wanted to know, or some other - you know, I kind of had a couple of trusted people. I was like, 'Who would you invite to this?' and got a big pool of people and reviewed information. And then when I invited people and then they found out I submitted Kickstarter, all these people started offering to send me printed stuff to give away as reward. Tim Dooley and Aaron Wilson gave me a bunch of stuff and John Hitchcock and Florence Gidez and all these people started just like sending me piles of stuff that I could be giving away to Kickstarter awards. So it's super successful. Got money. And then, yeah, mounted the - got a bunch of volunteers, because again, I couldn't pay people to help install. But I had like a group of community volunteers. And I decided, right next door to my studio at the time was a little gallery space, very DIY. And we had like a little pop up show, a SUNY Albany printmaking grad student had a pop up show there. Oh and there was even, like, another space, kind of the boutique-y risograph, screenprint, stationery shop, or like, oh, we can put stuff up here, like a student show there. So it was actually like a citywide sort of thing that first year, and we just documented the hell out of it so we could put together a good grant writing for the next biennial.

Miranda Metcalf That's super smart. You know, I didn't realize that, because I know that we talked about that you've gotten some nice grants to do this. But to kind of rely on community the first go, so then you really have something meaty to show grant panels, is quite a nice way to do things. And then that way, you don't have to kind of rely on wearing out the kindness of strangers, right? Because you do it the first year, people are going to be really excited. You're doing it in two years time. They're like, 'Oh, I kind of gave to this last year,' you know, there's, you're going to probably not get as much resistance just because of the novelty wearing off.

Nathan Meltz Yeah, the one person who is actually like a trained installer, who, she donated her time to first biennial, by the second one, I was able to pay her for a week of work. So, you know, they definitely tried to make it pay off for people. And yeah, I think it's like those grant agencies, you know, so two years in a row I've gotten lucky enough to receive grants in the International Fine Art Print Dealers Association. And, you know, I think a lot of grant apps, they have a little section for your supplemental material, which can be kind of whatever and then it's all, like, the photos that, you know, I had students taking and video stills and links to YouTube videos. And I think all - yeah, I think all that stuff helps to show that you can actually pull off a project. Because I think a lot of people don't want to give you money if you haven't done it before.

Miranda Metcalf Right? It came to be through basically just making it happen, you know, seeing a need and then being willing to put in the hours and being willing to just put in the asks to make something happen.

Nathan Meltz Yeah, there's something - the first one was definitely really punk rock in terms of just doing it yourself. And, you know, I live in this post-industrial town where it's easy to get spaces. And there's sort of an ethos of doing it yourself. And then the second biennial, 2016, wasn't any big step up. We had money, but it was at, like, this art center, and then this other gallery, which was nice, but it was still a lot of relying on volunteers. And people like Terry James Conrad, who's now over at Iowa, working like a boss to help me install, and a lot of people still volunteering. And you know, it finally, it's gotten to the point where it's, you know, it's gonna be hosted by this endowed gallery, and some more things are paid for, but certainly it's a labor of love. This is all, I'm just doing it because this is what I - this is the art show that I want to see that no one else is doing right now.

Miranda Metcalf I love that idea of making something because that's what you want to consume. That was definitely part of when I decided to start Pine Copper Lime (Hello, Print Friend), is I kept thinking, why isn't there just a cool website, where when I'm on the bus, I can go to it and I can just read about something interesting in printmaking that I hadn't heard about before?

Nathan Meltz And no one else, no one else is doing it.

Miranda Metcalf No one else is doing it!

Nathan Meltz So we need you, Miranda!

Miranda Metcalf And so, there was something else that I wanted to talk to you about, because you mentioned your location as being a place that helps make the Screenprint Biennial successful, just in terms of space. So being - Do you mind if two people know the name of your town?

Nathan Meltz Sure, sure. I'm in the post-industrial city of Troy, New York. Which, up and through history right through the 18th century, was vying with New York City to be the largest populous area on the East Coast and the shipping capital of the East Coast, and then lost to New York City. But it was kind of like a rich steel town throughout the 19th century, and shipping town. And there's a huge whaling industry just south of us in Hudson, New York. But now it's, you know, it's very much an economically depressed area where there's a lot of empty buildings, you can get cheap studio spaces somewhat. And it is what you make of it. But, also, things don't come here. So if I want to see my print friends, you know, because we talked about the community, you can try to do something in which I get my friends to come to me, which is also like a byproduct of the Screenprint Biennial that I didn't intend on. What really ended up happening, where we have a symposium that coincides like the day after the opening receptions, and then we usually have a round table and maybe a keynote and other activities. And we've been really lucky, there's always like a dozen printmakers from all over the country that usually come to Troy and we do activities and hang out. And it's like a little mini conference. And it's really rewarding and fulfilling.

Miranda Metcalf I think that that's such an important part of building the community that we were talking about, too, is that we are a community of people who really don't mind doing it ourselves when that's necessary. Sort of, you know, being someone with a creative practice and, you know, in, you know, a smaller city, a city that maybe doesn't have a lot of resources, I feel like there's a lot of printmakers out there who are in the same boat, because a lot of us are in academia in some way. And so we ended up going to where the jobs are.

Nathan Meltz Yeah, and so you have people, like, you know, far west of the country and in small cities, but then they do things like the - and I only remember it as the name that I tease Kevin Haas with - the, I call it the Rocky Mountain Print Militia, but I think it's Rocky Mountain Print Alliance. And they have, like, several days of programming and they do all the cool stuff for people that are in that region. And a couple people just started, I think Justin Diggle has been heavily involved in that, who is, you know, at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, so people build it. I think people - maybe it's printmakers, we're so used to being on the fringe anyway, you know, we're so, you know, when I go to Chelsea I see prints everywhere, but they're always labeled as paintings or, you know, anything besides what actual print they are. And so we're so used to being on the margins anyway, then we've just made up little base camps along those margins and claimed it for our own I think.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, yeah, I love that. So sort of speaking of being on the margins, having your practice based in screenprint and having a Screenprint Biennial, which really does show people who are pushing the boundary of work, people who are just technically really amazing - was part of that motivation for doing that to maybe carve out some legitimacy for screenprinting, which may be sometimes even, and you know, not to offend, but maybe sometimes even within the printmaking community might be a little bit on the margin of that as well? You know, in the sense that people do have that, as you say, band poster, t-shirt, you know, association with that.

Nathan Meltz I have a good friend lithographer, who I won't name, and he does it sort of jokingly, but he's described screenprinting as the "mac and cheese of printmaking," it's gooey and easy and everyone loves it. And there's a certain truth to that, you know, like the learning curve isn't that hard, to get basic ink through a matrix onto paper or substrate. But yeah, part of it was that screenprinting is, I think - there's a good argument that screenprinting is more hybrid than other art forms, that it really works well for installation because of its immediacy, in sculpture, because you can print on this variety of substrates. But that's not totally true. Because there's great artists, have you heard of Mizin Shin? So you know, her own work is like, you know, amazing, and she will make sculpture and sometimes she'll do screenprint, but she has these giant relief prints that she's made into wallpaper for installations that come from vector graphics. So she's kind of, like, she totally debunks that argument. And I think a lot of print is very hybrid like, and my goal was just to show that all this stuff that's going on in the art world right now, that is already print, just trying to claim a little bit of that and take some credit for that. And say, you know, what you're seeing in these galleries, people that are working as assistants for other people, or just, you know, artists that are using printmaking. Let's claim it. So, you know, there's great people. And I'm not saying he hasn't like, pushed out printmaking, but like, there's great people like Hank Willis Thompson, who does all these great prints at the Lower East Side Print Shop. But you read about him, and the first thing it'll bring up, probably, is photography. When I think he's doing some amazing prints that are really experimental, and kind of couched in a social practice. So I'm just, with hybrid, I'm just trying to kind of show off what screenprint can do. And it could, you know, the only reason it's not just print in general is because I decided to start with screenprint, because that's what I know. And there are other print biennials of all sorts but just no screenprint so far.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, definitely. And I think it's, you know, at least from my perception, I think it's done that job, in the sense that it exists as a marker of sort of where printmakers are with this particular niche within our niche. And seeing that really high quality work collected in one place, you can't deny that within that exists a well of of great artistic talent. So I think it's great that it's there, and it's doing its job.

Nathan Meltz Thanks. Yeah, I've, you know, that's that's the goal. That's the dream.

Miranda Metcalf So we've talked a lot about the the Screenprint Biennial and a little bit about your practice as well. I'm just sort of thinking about, you know, one of the things that I've been curious to ask artists when they come on is, if there's anything that they never do get asked that they wish they were. Is there any sort of aspect about their work or their practice people seem to miss, and you know, kind of just to give them a sense of like, now is... you can talk about that.

Nathan Meltz Wow. That's a really hard question. What do I wish people would think about? ... I kind of wish we could come back to this question, but I don't know if I - I don't have a good answer for that, Miranda. Yeah, I'm kind of drawing a blank right now.

Miranda Metcalf That's fine. I've tried asking a couple other artists, just in conversation, and it seems to be a difficult question. Which is interesting, because maybe so much of how people talk about their practice, and even really form almost their own ideas about their practice, is in conversation with other people. And so you know, to sort of be asked anything outside of that is a little bit tricky.

Nathan Meltz Like you're asking me to step outside of myself, almost, and look in. Like an astral projection. I think for me, so maybe I could, I could flip this and the question - there's something, something I'm interested in that I don't get to talk about enough, is the struggle between... and I bring this up to other artists all the time. In fact, when we've had Screenprint Biennial symposiums, I'll make this question sometimes, is, you know, what is your obligation to be political? How do you situate yourself in the world of political prints? Because printmakers talk about this all the time. And I think it's just so hard to make good political work, and I don't, I think I fail a lot of the time. And I would like to know how to do that better. So that's not something I really want someone to ask me, because it's about my failures, but that's a conversation. If I was like, if I was gonna ask someone, I would ask that, like, how is that done? It's just some people who are, you know, Josh MacPhee is wonderful at it and in a totally different media, Paolo Pedercini, who's like, does political video games at Carnegie Mellon, has this great kind of thought that, you know, the lowest hanging fruit of political art is just to make art about politics where the goal should be to have art that is involved in politics.

Miranda Metcalf Maybe you can speak to, a little bit though, you know, because your work is political and has this sense of narrative and message. Do you really feel sort of, you know, an obligation to be political? And are you like, 'well, if I, you know, if I really had my way, and if things were going well in the world, I'd go make landscapes, but, you know, I do feel this, this need to do it?' Or sort of... maybe just speak to that a little bit.

Nathan Meltz Yeah, I'm gonna bring up Josh MacPhee again. Because at one time, he asked me for his Paper Politics show, why I even made prints in the digital world. And I said, 'Well, we live in a world with bodies. And as long as we have bodies, we will want to have the physical artifact to reflect against,' or something to that effect. And so then I'm going to kind of take a version of that and say, we live in a political world. And as long as political forces of male patriarchy and statecraft and colonialism and state sponsored violence and incarceration and all those other things happen, we have to react against all that. If you don't react against it... and I'm also, this is a great little bit from the Josh MacPhee's Signal Magazine that he co-edits. And their mission statement is something like, everything we do - and I'm just totally paraphrasing probably poorly, Josh, I apologize - but it's something like, everything, you know, all art is created in an environment in which, if you are the status quo, you're basically making art in a situation of patriarchy, violence, all these other things, unless you make a, like, decisive idea and decision to work against that. And you can. And I think as artists, we live in this world that's terrible! And thus, as long as it is, we and I will make an attempt to make art that responds to that.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, that's, that's really great. And that actually kind of speaks to something that really been present in my mind in the last few months since moving to Australia. One of the main questions that we get here by Australians, or really anyone, is "Do you think you're going to go back?" Meaning go back to America. And that's tricky. Because I, as I receive information coming out of the states, just have, you know, the growing dumpster fire vision in my head. And that's really difficult. You know, at the same time, I became an aunt last week, you know, my brother and sister in law had a baby, and she just represents this life. And you get this really sudden sense of what am I going to do to make that life okay? So, if everybody just leaves and doesn't push back and just sort of walks away, and comes and stays in sunny Sydney, with the beaches and the socialized health care, what really happens to America? And what obligation do I have as an American? You know, I think that people can be glib about that identity, maybe more so than other countries even. But I was born there. And my my family, you know, the colonizers that they are, they've been there for for a few generations, at least. And what is that obligation to go back and try and make it better? Whether it's through making political work, or creating resources in the arts, or anything like that. And it's, it's sort of refreshing to hear your take on it. And nice to hear that it's just, no, like, I'm here. And this is my obligation. And I'm stepping up to it. And that it is a significant act, even if it seems... it's so easy to get disenchanted and feel extremely disempowered and start to feel kind of hopeless.

Nathan Meltz Yeah, and I think there's, even beyond the world of printmaking, there's, you know, I do think just as artists, people have many ways to make a better world, like for three years, I had a free after school arts program. That was also grant funded, for kids in an underserved neighborhood at this old community center. And with the mission of basically let's, you know, like the sweet art classes kids can have at the, you know, at the art center that's downtown, which costs a lot of money? Well, this is the same set of instruction, but like, every kid can get it. And we had a really diverse outpouring of kids and like the last season, we had a good part of the season like, man, there's a great group of kids that very much, like, represented the future, what the future is going to look like. And it was very inspiring, just knowing like, okay, it's not all bad. Because you know, the reason that there's a lot of people, ticked off, reactionary, aging, and not-so-aging, white dudes that are really angry, is they don't like the new face of what the country's gonna be like. And as artists, we can help by reaching out to everyone and trying to welcome kind of the next generation.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, that's super significant. I love that. And so kind of thinking about that sort of as it relates to the aesthetics, in your own practice, the bodies that you use are robot bodies, the sentient beings who are who are being affected in the world that you create, are ageless, classless, genderless. Was that sort of a conscious decision in your way? Or does it have to do with maybe a dystopian future that you're more interested in that can be kind of a warning?

Nathan Meltz Sure. Sure, it's definitely the attempt to put everything through a lens of 21st century technology. So we talked, you know, I have images talking about agriculture, and it's robot cows or a robot farmer or I'm showing war and I'm really amping up the technology that's used and, you know, lately all the prints I've been making are digging through the archives of The New Masses, which is this great hyper-lefty anarchist publication that was out in New York City from early '20s into the mid '30s, is at least what I've been digging through. And you know, there's lots of William Gropper illustrations and people working in that kind of genre of like highly political figurative drawings and lithographs, and trying to make work that responds to those works. But then thinking, like, well, what is this gonna look like now? For the 21st century? So the idea of, you know, I have, you know, this great William Gropper illustration of a giant hand and it's kind of holding up against like, you know, Old World War One era tanks and biplanes. And I've made this giant robot hand with repelling, you know, contemporary tanks and drone pilots, and trying to re-envision those through contemporary lens. And so, you know, I'm looking at - recently, I'm working on this project, this exchange portfolio in which artists have been asked to respond to various works by Kathe Kollwitz. And so looking at that work and how great she was to the figure, and now I'm trying to translate, you know, some images and some of those concepts into robot figures. But yeah, they're fairly genderless, sometimes they're not human. I have octopi, pigs, and it's the idea of like, just, that's how I want to make a world through this lens of technology.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, I watched the motherboard video.

Nathan Meltz Ah, my robot porno.

Miranda Metcalf Yeah, the robot porno, which is great fun. I highly recommend it. As I'm watching it, you know, you've got the two stars of it. And you're sort of trying to ask yourself, okay, which one's the male and which one's the female? It's not entirely easy to figure that out.

Nathan Meltz Yeah, in my mind, there was a gender, one was gendered one way, one was the other. But I ended up showing them to many people, and it was different from my intent. So I just rolled with it. So you really can't tell, you know, their sex is revealed at some point. But yeah, it ends up being a piece about gender and not totally intentional. But I like the fact that that's how it's read.

Miranda Metcalf Right. Well, that's such a huge part of the creative act is that so much of it takes place internally, and that's one half of a creation's life. And then the other one, of course, is in its reception, where that conversation between creation and receiver, or object and viewer, really creates the meaning, insofar as an object can have, like, one defined meaning, which is super fascinating, I think, about the creative process. I realized we're coming up on an hour mark. So -

Nathan Meltz Yeah, nobody wants to listen to me that long.

Miranda Metcalf I would love for you to tell people where they can find more about you and get in touch.

Nathan Meltz Okay, everyone. Thanks for listening, and you can find links to everything at nathanmeltz.com. You'll see links to the Screenprint Biennial, which brings you to screenprintbiennial.org, which, for those of you who are art teachers, I've heard it's a pretty good resource for teaching stuff. And to my website, you can find links to my SoundCloud page, and, you know, it's all there. nathanmeltz.com. And thanks for listening.

Miranda Metcalf I will put all of that in links in the show notes as well, so you can find it that way. And thank you again, Nathan.

Nathan Meltz Miranda, thank you so much. This was fun.

Miranda Metcalf All right. Thank you.