Reinaldo Gil Zambrano | stories for home

Written by Miranda K. Metcalf | Published 8 oct 2019

What is it to have a sense of home? What are the feelings that makes up home? Is it safety? Ownership? The people who you find there? Reinaldo Gil Zambrano’s prints explore these very questions. Zambrano is a traveler, a storyteller, a printmaker and a community builder. In his practice all of these identities weave together until they become interchangeable and deeply effective and affecting.

RGZ and The SoulCrafter 2016. Photo by Ashley Rae Vaughn

Zambrano grew up in Caracas, Venezuela, drawing in his notebooks, on the walls of his home, and his favorite Dragon Ball Z cartoon characters in front of the television. When he wasn’t drawing, he was getting lost in the children’s books his mother bought him from the famous Venezuelan illustrator Rosana Faría. The power of visual communication in Faría’s illustrations is something that has never left Zambrano. The idea that drawings can be vessels for story telling is still at the heart of his printmaking practice.

During his childhood, the biggest economic driver in Venezuela was the oil industry. His classmates dreamed of growing up to be engineers, and while his parents were supportive of his artistic endeavors, even allowing him to paint on the wall of this bedroom, they asked that he first go to a high school that focused on science. They promised that after he graduated he could then do whatever it was that he wanted. After a few years of slogging through biology classes and feeding his artistic heart by painting backdrops for the theater department, he was all well on his way to become - he assured me - “the worst architect ever.” Things changed when Zambrano received a scholarship to study at the United World College in Costa Rica from which he received International Baccalaureate diploma. It was there that his life was set on a course that would eventually lead him to an MFA, a marriage, and becoming a beloved and much-needed community builder in Spokane, Washington.

Thus at the tender age of sixteen, he packed up from Caracas and moved to San Jose to study at the college. When I asked him if this was a difficult thing to do at such a young age, I clearly heard Zambrano beaming on the other end of the line. He told me it was best two years of his life. There were 75 students in his cohort from 72 countries at United World College. The major languages of the institution were Spanish, French, and English, and at the time Zambrano only spoke one of these. His early interest in visual communication came in handy as he learned to communicate and connect with his colleagues through drawing. “Even beyond the limitations of language, we were able to find and share this common experience. Share them and laugh and become friends,” he remembers fondly.

Encuentro, Relief Print on Paper, 32 x 26 in, 2019

Zambrano went on to study art in undergrad, but it wasn’t until graduate school that he was introduced to and fell in love with printmaking. It was 2014, he was studying at the University of Idaho in Moscow, and making large-scale charcoal drawings. A fellow student named Tim Han asked him if he had ever tried printmaking, as Han could see that Zambrano was interested in creating a graphic quality to his art works. Han showed Zambrano beautiful Korean woodblock prints, which he had brought with him from Korea. Zambrano was completely taken with the images and tried his own hand at the practice. From there it was only a matter of time before Zambrano experienced his first magical moment seeing the paper separated from the block. He was hooked for life.

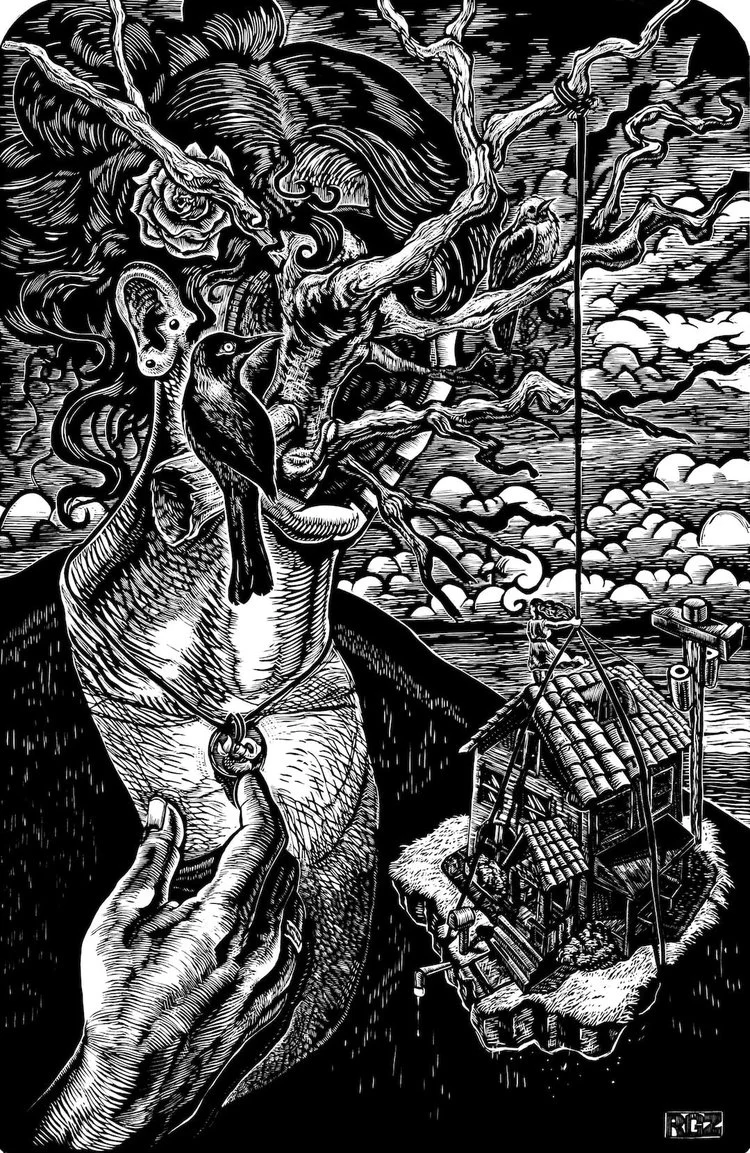

Zambrano’s current practice is about the idea of home, the practice of magical realism storytelling, and where they all intersect. “In Venezuela, telling a story is an important part of everyday life,” he tells me, “it is the treat that you get when you bring a new person to your table.” He describes himself as a collector of stories from those around him, those which are shared over a coffee or a beer. The collected stories start growing in his head and he creates visual narratives within one frame which he carves into his blocks. He loves the large format because of the freedom of mark making but also because of its ability to absorb you when you stand in front of it. Just like being pulled into a good story.

Childhood Ornaments, Relief Print on paper, 55 x 36 in, 2018

Yet unlike a verbal storytelling, Zambrano reveals visual story telling’s ability to create a universality of experience. Zambrano tells of creating an image of the slums of Caracas and having people from Palestine to Brazil see it as being of own their homeland. This is the power that the visual story holds. It can be specific to the creator, while at the same time being personal to the viewer. Everyone will bring their own experiences to the image, and it allows the work to be transcendent and universal. Verbal storytelling is linear and bound to the constraints of time, and the necessity of a beginning, middle and end. A visual story, however, reveals itself to the viewer like a spider spinning her web. The image has a center, but the eye can flow out in any direction. Zambrano takes his collected stories and repurposes them for his own creative practice by throwing in his own storytelling and his taste for magical realism.

Magical realism runs deep in the narrative tradition of Latin American culture. While some may see it as simple exaggeration, it is more complex and more functional than that. To tell a story in this way, is to imbue the story with staying power and fable like didactic powers. While the context of the story may be common, stories become bigger than life and resonate in our memories through the way they are told. Zambrano illustrates function of stories by telling me a family legend of the cousin who once ran through a closed sliding glass door. The story should be familiar to most, many families have their own version of it: a precocious child ignoring directions about not roughhousing in the home, runs right into trouble. Yet when the story is told in Zambrano’s family, the kid smashing through glass in slow motion, bits of glass fly through the air like pieces of candy “from a piñata no one wants to eat”, and while the child should have been killed, he escaped with only a few cuts on the back of his legs and his epic tale is lauded as the child narrowly outwits death. “To tell a story this way, the common becomes extraordinary,” Zambrano says. A story like this gets told and retold, the details get perfected and it solidifies not into the story of the young boy, but the story of ‘us’. A story, among many, that makes up a community, and it is a community that makes up a home. Stories are used by community members to express who they are. It is this use of stories as community building and home-making that Zambrano captures in his prints. “Home is what you create with those around you,” he says.

But what of printmaking in Zambrano’s home town? While writing his MFA thesis, Zambrano looked to write about printmaking in Caracas, but couldn’t find anything online. As unlikely as it seemed, as far as the internet was concerned Venezuela was a printmaking wasteland.

Luckily things changed with an invitation from an early hero, Rosana Faría, when she sent him an invitation to participate in an exhibition at a printmaking shop in Caracas called TAGA. A shop, which up until this point Zambrano had not heard of before. On his next visit back home the following June, he made a trip to visit TAGA and was blown away with what he saw: a beautiful house filled with printing presses. As it turned out, Caracas has a rich printmaking tradition, there is just no one writing about it. Zambrano hopes to change all this and continue to research the studio whenever he travels back to his hometown.

Emancipacion, Relief Print on Paper, 36 x 24 in, 2019

Zambrano’s sense of home is a moving target, Caracas to San Jose to Idaho to teaching at Eastern Washington University in Spokane. For those of you who haven’t lived in the Evergreen State, you might remember little ol’ Spokane from episodes of “COPS” from the 1990s or as the home city of notable musicians such as Bing Crosby or Keyboard Cat. Zambrano recalls quips he has heard over the years since moving to Spokane, such as “What do you mean Spokane is a printmaking town? Don’t you just go there to be stabbed?” But Spokane is experiencing a renaissance, like many mid-sized and affordable towns the young and the creative are flocking there for the accessible housing and elbow room to build something for themselves. “People show up here,” Zambrano says, “I host a printmaking event and people come. If there’s a new brewery that opens, it will be packed. The people here are looking for community and they will show up to find it.”

Zambrano has come to the right place at the right time, with talent and enthusiasm to make it all work. He was carving a large linocut print on the floor of his kitchen when he realised how badly Spokane needed a printmaking facility. Like many of my guests he rightly points out that the base of printmaking is in universities and once students graduate, many of them are forced to let their practice stagnate without proper access. Zambrano received a grant from Spokane Arts to open RGZ Prints. A small shop in downtown Spokane where he can do his own work, but also use it as a base to bring others into the process. Once he started to set up shop, he was contacted by a group of letterpress artists from Millwood, a community on the outskirts of Spokane who were looking to move into the downtown. Shortly thereafter they joined forces. RGZ prints went on to welcome Derrick Freeland, an animator, illustrator and board game designer as well as Dorian Karahalios, a master bookbinder. Together the group formed Spokane Print & Publishing Center, a nonprofit with the primary goal to educate Spokane and the surrounding community about the process of printmaking and invite them to explore it. Spokane Print & Publishing Center boasts presses for relief, intaglio, and letterpress as well as screen printing, book publishing, board game design, illustration, digital printing, and book binding. Zambrano is looking to expand on this, so if anyone in the Spokane area is reading this who knows of a press looking for a good home, let him know.

If this wasn’t enough, Zambrano is also the organizer for Spokane Print Fest, a month long event held in galleries and studios throughout the city filled with live printing, student demonstrations, and gallery exhibitions. All of this made possible due to a collaboration with the non-profit Terrain. The whole event celebrates printmaking for a full month and educates people about the craft. Every Saturday throughout the month of April there is a different workshop at a different gallery focusing on relief, monotypes, pronto plate, or other forms of intaglio. The whole event was such a success this year, that he will doing it again in 2020 with even more support and involvement from the universities to showcase students and professional printmaking at the same time. All of this is done with an eye towards educating the public and developing a deeper market in Spokane to truly put it on the maps as a printmaking town.

The Soulcrafter, Relief print on fabric, 62 x 45 in, 2017

At the time I recorded the interview with Zambrano we were both recovering from colds and talked about how important it is to have a community to take care of us when we’re sick. Yet, while we live in a time where we are connected to hundreds and thousands of people throughout the world through social media, many of us don’t have someone to call to bring us orange juice when we’re under the weather. Luckily, I think we are in the process of pulling our heads out of the digital sand. As a society, we dove so quickly and deeply into the wonders of internet connection over the past two decades that we are just now coming up for air. While seeing photos of our nieces everyday growing bigger and cuter even though they are on another continent is a goddamn miracle, we still would like someone to sit across a table with and share a story and a drink. We want to build narratives that make up an “us” that is across the street as well as across the world. For it is in our stories that we create our sense of home, and it is in our homes that we can create the stories that grow so large and perfect that they will outlive us all.

more information: