Wuon-Gean Ho | little linos

Written by Miranda K. Metcalf | Published 31 Oct 2018

When speaking with Wuon-Gean Ho it quickly becomes clear that she is an unusually thoughtful person. Her words are carefully chosen and delivered through a gentle Oxford accent. She attributes this quality to her work as a veterinary surgeon, where she is well aware of the weight her words will carry, words that may stay with pet owners for quite some time. Her artistic practice has the same intimate feeling. She likes to work in series, moving through the images until there is nothing left to tell, and it is time to take on something completely different. This could give the impression that there are large jumps in her subject matter and in her aesthetic, but in truth they are all reflections on her own experience. So for Ho, perhaps more so than other artists, in order to understand her work you need to understand her story. That story is of a life informed by an unusual upbringing and a somewhat indirect path to printmaking.

Ho was born in Oxford, the daughter of expat parents from Singapore and Malaysia. Her childhood home was next door to the family veterinary business, where her father worked as the surgeon, assisted by her mother who was the nurse. Her parents tell her stories dating back to before she can remember, of her sitting on her father’s lap while he performed routine surgery (which she laughingly admits might not have been ideal). It was in childhood that she first encountered printmaking. At age 11 her family attended an art fair called “Art in Action”, an annual festival of arts and crafts set in the middle of the Oxfordshire countryside. It was there that she created her first print: a linocut of a cat on a roof, an experience that filled her with delight. She speaks fondly of coming to understand that printmaking is about the making of a matrix from which multiple images can be produced; to this day she loves the challenge of working back to front and upside down. After this experience she began making prints at her Mum’s kitchen table, an art making practice which continued right up until the time she left for university to follow in her father’s footsteps, with the understanding that one day she would take over the family business. Ho continued to make prints through veterinary school, offering her skills to the many amateur dramatics groups in Cambridge to make promotional posters for the cost of the ink and the paper.

The will and the want to create has stayed with her through college and after, until she took up her own veterinary work, which she still practices. I was curious to know where she thought her creative output came from, seeing as both her parents were working in the maths and science fields. In answer, she delicately pointed out to me the false dichotomy of the artist/scientist. She said, “There’s this idea that the scientists are holders of the secrets of life and that artists are the dreamers, but scientists think creatively, and all arts, and perhaps particularly printmaking, are subject to scientific rigour.” She went on to say that printmakers can build a beautiful theoretical scaffolding around this practice, but to do so forces us to be very specific about what is in fact a very loose and potentially organic way of art making. While theory helps combat the commonly held view that arts are vague and optional, she believes that artists are all the more productive when they don’t have to constantly justify themselves.

In relation to Ho’s veterinary work, she speaks of what a privilege it is to have access to an intimate way of seeing animals and getting to know the very different kinds of relationships people have with their pet. She describes seeing people treat their animals better than they treat themselves. In some cases, she wonders if it is because they would like to treat themselves with that kind of love and respect, but for one reason or another don’t feel like they can. While there are some people who see their pets as status symbols or even an avenue for monetary gain, she has also seen those who have postponed weddings over a sick companion, and many who deeply mourn the loss of a friend, whether it be a dog, snail or chicken. I believe that these experiences affect the way animals appear in her prints. Rather than being decorative or symbolic, the animals in Ho’s work show up as the protagonists, each with a specific purpose and intelligence. For instance, an earlier series she created was the “Spirit Guardian Series”, filled with images of women tenderly holding an animal, or perhaps, being tenderly held. Rather than serving a decorative function, as animals so often do in art, the animals and humans look like communing souls, and the actual protector could be either one of the pair. She is uninterested in superficial admiration for animal beauty, instead, Ho gives her animals agency, and allows them to become a metaphor for the unspoken, spiritual or vulnerable — a representation of the mysterious other.

Her latest body of 65 prints was made for just one person, her father, though in this age of social media her audience has been greatly expanded by Instagram and Facebook. The working title for these prints was “Diary Prints” (2016–18) and had strict parameters: each measures 15 x 20 cm (6 by 8 inches) with a maximum of two colours, and were to be made quickly, at a pace of an image every fortnight or so. Many of these prints are little vignettes, and her presence, implied or actual, is in almost every scene. To understand how she came to make these prints, one needs to know about a film she was making in art school, “Stoke Junkie”. Having enrolled at the Royal College of Art as a mature student in 2013, she wanted to make a film to learn new techniques. Being aware that in the UK one hardly ever sees elderly non-white people in the media, she decided to turn the gaze towards her own parents. Beyond this interest in their representation, Ho has a clear love and admiration for her mother and father and their unique points of view. Her dad at the time was still a bodybuilder at the age of 75, and her mother an outspoken, playful tai chi practitioner, who builds elaborate scaffolding for her beloved “Queen of the Night” flower out of curtains and coat hangers. Her mother’s health had been declining for the past six or seven years and her father had recently retired to take care of her. During this time, her mother would often joke that, tired of living, she was going to find a drug dealer in Oxford who could give her enough cannabis to overdose (despite Ho’s gentle insistence that she’s pretty sure that’s not how it works). Their wonderful irreverence and dark humor was supposed to be the subject of the film but it turned out to be quite different. In the midst of making the film, one Saturday morning, while her father was out jogging, he tripped on the root of a tree, fell against it, and broke his neck. Since then he hasn’t been able to stand or walk. The after affects of this sudden and unthinkable change to all their lives is captured through the film and the finished piece can be seen in its entirety on her website. [link] She speaks quite beautifully about the power that filming had to displace some of the emotions she was going through watching her parents navigate this most unexpected tragedy. She says “[The act of] making is a good way to stepping into the moment, and forgetting about the future or the past.” Through filming, she could be completely focused on what they were saying or doing, and put aside sadness and fear.

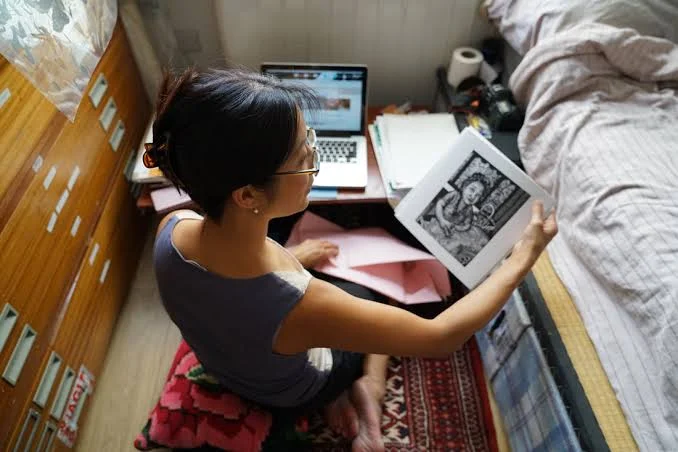

Ho’s father has been in a care facility since the accident, and has understandably become withdrawn from the world. Ho found that during her visits the conversation remained on the day to day, because anything outside of that was painful reminder of what he was missing. Her “Diary Prints” came to serve a specific and beautiful purpose: they were a way to bring in visual representations of the outside world, something for him to ponder, filled with clues and hidden narratives. Being that he was by nature a joker, and master of the terrible dad pun, Ho’s linocuts speak to this side of his personality. They are most often smart, funny, focusing on the absurdity of life: the obsession with smart phones and hedonism, a self deprecatory and situational hilarity. I think she is admirably aware that they are done within the father/daughter paradigm: the woman who is represented in the prints is a sanitized, comical self, much more innocent, youthful and carefree than in reality. This makes them stunningly unique works of art, created with a single person in mind, and from a place of unconditional love.

Much more work (and even better writing about it) can be found on Ho’s blog --an uncommonly well written and entertaining artist blog. https://www.wuongean.com/